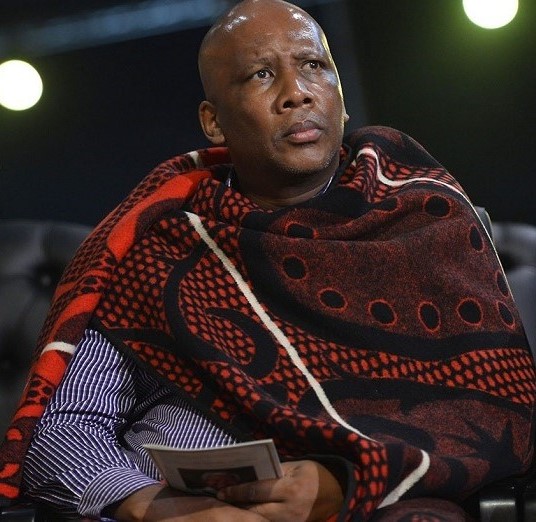

Chris Mokolatsie

Mbeki in Maseru: More Than a Tribute

Last week, in Maseru, former President of the Republic of South Africa, Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki, delivered a memorial lecture to mark the thirtieth anniversary of the passing of His Majesty King Moshoeshoe II. Delivered on 14 January 2026 under the title A Tribute to Exemplary African Leadership Which Africa Needs!, the lecture was notable not only for its commemorative intent, namely a ceremonial reflection on a departed monarch, His Majesty King Moshoeshoe II. Underlying the entire lecture, one detected a common theme, namely the historical question of Lesotho’s relationship with colonial-era South Africa and post-apartheid South Africa.

In this sense, the lecture was a profound historical and political intervention that re-centred, implicitly and deliberately and unapologetically, one of the most sensitive, emotive, and persistently avoided questions in Basotho public discourse: what should be the future relationship between Lesotho and its neighbour, South Africa, today in the post-apartheid era? The lecture left lingering political and historical questions that Basotho society, for a long time, have avoided and preferred to keep unresolved, if not entirely unspoken.

Beyond the “Tenth Province” Myth

For many years now, this question has existed in the public imagination only in caricatured form, most commonly reduced to the deliberately provocative suggestion of Lesotho becoming South Africa’s “tenth province.” While this framing may generate social-media clicks and provoke emotional reactions, it trivialises a matter of profound historical, political, and moral consequence. It obscures rather than illuminates the real issues at stake. What is required now is a sober, deliberate, and well-thought-out public discourse. Such framing, while effective as political theatre and social-media entertainment, does little to advance serious reflection. It substitutes spectacle for analysis and outrage for understanding. Yet the persistence of the trope itself is revealing. It suggests not that the question is frivolous, but that it remains unresolved—and unresolved questions have a habit of returning. What is required now is a sober, deliberate, and well-thought-out public discourse on the matter.

What Mbeki’s lecture accomplished, perhaps unintentionally but unmistakably, was to re-centre this question within a longer historical frame, one that predates both apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa, and indeed the modern nation-state itself. In doing so, it challenges Basotho to reconsider not only their future, but their past—and the assumptions through which that past has been interpreted.

Memory, Sacrifice, and the Heart of Lesotho

At the heart of the debate lie two broad and opposing positions among Basotho. On the one hand are those whom I shall, for the purposes of this discussion, call nationalists. Their argument is rooted in a powerful and emotionally resonant historical narrative: that Lesotho was forged through the blood, sweat, and sacrifice of the Basotho people. Lesotho is the historical product of struggle and political ingenuity under the leadership of King Moshoeshoe I. Surrounded by hostile forces, imperial Britain, Boer expansionism, and the violence of the nineteenth-century regional order, Moshoeshoe secured, through diplomacy and resistance, a political space and sovereignty within which the Basotho survived as a people and the territorial foundations of the nation we inhabit today.

From this perspective, any discussion of political union between Lesotho and South Africa as two independent modern states is read as a repudiation of Moshoeshoe’s achievement, if not a moral transgression. It is dismissed as bohlaba-phieo—a betrayal not only of the founder, but of the historical suffering through which Basotho nationhood was forged. This position, championed by the likes of Ntate Moorosi Moshoeshoe of Naka la Mohlomi, carries emotional force, and its persistence is understandable. Nations are sustained as much by memory as by material conditions. This position cannot and should not be dismissed lightly. Nations are built not only on borders and institutions, but on memory, sacrifice, and shared meaning. To underestimate the emotional and symbolic power of sovereignty is to misunderstand the foundations of Basotho nationalism itself

On the other hand, stand the unionists, or pragmatists, and realists who argue that history and reality, when examined honestly and without romanticism, point not to isolation but to deeper integration, cooperation, and possibly even political unity between the two countries. This view, less emotionally mobilised but no less historically grounded, argues that this nationalist reading may be incomplete. Proponents of this view, among them respected thinkers such as Ntate Pali Lehohla, argue that Moshoeshoe I was not a nationalist in the modern sense, but a regional political actor whose strategic imagination extended well beyond the boundaries of present-day Lesotho.

It is this interpretation that Mbeki’s lecture implicitly advances. Central to this argument is a re-reading of King Moshoeshoe I himself, not as a narrow nationalist in the modern sense, but as a sophisticated regional thinker who understood Lesotho within the broader political geography of Southern Africa. As Mbeki’s lecture compellingly demonstrates, Moshoeshoe did not conceive of Lesotho as an end in itself. Rather, Lesotho, as a protectorate and later as a state, was understood as a contingent political space within a wider Southern African struggle. As Mbeki observes: “The Protectorate could not be an end in itself, but as part of a wider African project of resistance, solidarity, and liberation.”

Tsohang bana ba Thaba Bosiu

As the lecture reminds us, in the poetic call ‘Tsohang bana ba Thaba Bosiu’, this was not an imposition on the Basotho but an affirmation of a role which King Moshoeshoe I himself understood and accepted that Lesotho, then a “Protectorate, could not be an end in itself, but a liberated area further to advance the struggle for the total liberation of both Lesotho and all its neighbourhood.” This assertion is deeply unsettling to conventional nationalist narratives. It suggests that Moshoeshoe’s vision was fundamentally outward-looking, and that Lesotho was never meant to exist as an isolated mountain enclave, detached from the fate of the region. Rather, it was conceived as a liberated African space with responsibilities beyond its own borders.

History offers further support for this interpretation. The bonds between Lesotho and South Africa, of culture, labour, language, kinship, and resistance, are far deeper and stronger than many contemporary Basotho public intellectuals are willing to acknowledge. From the migrant labour system to shared struggles against colonialism and apartheid, the lives of Basotho and South Africans have long been intertwined in ways that defy neat and rigid national boundaries, which is why I have argued for the abolition of the border between the two countries as a starting point.

Politically, too, this interconnectedness is unmistakable. His Majesty King Letsie II played a prominent role in the early establishment of the African National Congress (ANC), then representing Africans from as far afield as present-day Zambia. The same ANC has governed South Africa for over three decades and remains the ruling party today, albeit in a coalition arrangement. If this shared political lineage does not constitute fertile ground for serious reflection about the future relationship between Lesotho and South Africa, it is difficult to imagine what would. Major General Metsing was brough into power largely by the support of Pretoria.

Closer to home, the pattern persists. When King Moshoeshoe II was accused by Chief Leabua Jonathan of political interference, he reportedly responded by insisting on the necessity of respecting a tradition established by Moshoeshoe I himself: that Lesotho must always discharge its responsibility to the peoples of Southern Africa as a liberated area. Once again, Lesotho is framed not as an inward-looking micro-state, but as part of a broader African political and moral community.

Facing the Unfinished Question Together

None of this is to argue that political union with South Africa is inevitable, but whether or not, given our history and reality, this is desirable. The question is not whether Lesotho should disappear into South Africa. It is whether Basotho are prepared to engage honestly with an unfinished historical relationship—one that continues to shape their political and economic realities, whether acknowledged or not.

If Moshoeshoe cherished a great alliance of African peoples to resist their separate conquest, then perhaps honouring his legacy today requires not defensive isolation, but courageous re-thinking. If his vision was indeed one of regional solidarity rather than insular sovereignty, then fidelity to his legacy may require intellectual courage rather than ritual invocation. It requires a willingness to think beyond inherited slogans and to confront the realities of power, dependency, and possibility in Southern Africa as it exists today. To do that effectively, we need to liberate ourselves from historically impoverished prevailing terms of debate, independence versus absorption, sovereignty versus betrayal.

What Mbeki’s lecture compels us to recognise is that Lesotho’s relationship with South Africa has never been simple, nor has it ever been settled. To pretend otherwise is to retreat into comforting myths. The challenge facing Basotho today is not whether to defend Moshoeshoe’s legacy, but how to interpret it responsibly under contemporary conditions.

In that sense, Mbeki’s lecture was less a commemoration than an invitation. Whether Basotho accept it remains to be seen.

Summary

- Last week, in Maseru, former President of the Republic of South Africa, Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki, delivered a memorial lecture to mark the thirtieth anniversary of the passing of His Majesty King Moshoeshoe II.

- In this sense, the lecture was a profound historical and political intervention that re-centred, implicitly and deliberately and unapologetically, one of the most sensitive, emotive, and persistently avoided questions in Basotho public discourse.

- Surrounded by hostile forces, imperial Britain, Boer expansionism, and the violence of the nineteenth-century regional order, Moshoeshoe secured, through diplomacy and resistance, a political space and sovereignty within which the Basotho survived as a people and the territorial foundations of the nation we inhabit today.

Your Trusted Source for News and Insights in Lesotho!

At Newsday Media, we are passionate about delivering accurate, timely, and engaging news and multimedia content to our diverse audience. Founded with the vision of revolutionizing the media landscape in Lesotho, we have grown into a leading hybrid media company that blends traditional journalism with innovative digital platforms.