In one of the starkest illustrations of deepening poverty in Lesotho, some schoolgirls are ripping apart the mattresses they sleep on to make improvised sanitary pads during their periods.

Teachers and community leaders say this desperate practice, a last resort for girls who cannot afford menstrual products, is driving repeated absenteeism and, in many cases, permanent dropout from school.

The crisis has prompted the launch of a national programme aimed at restoring dignity to thousands of adolescents.

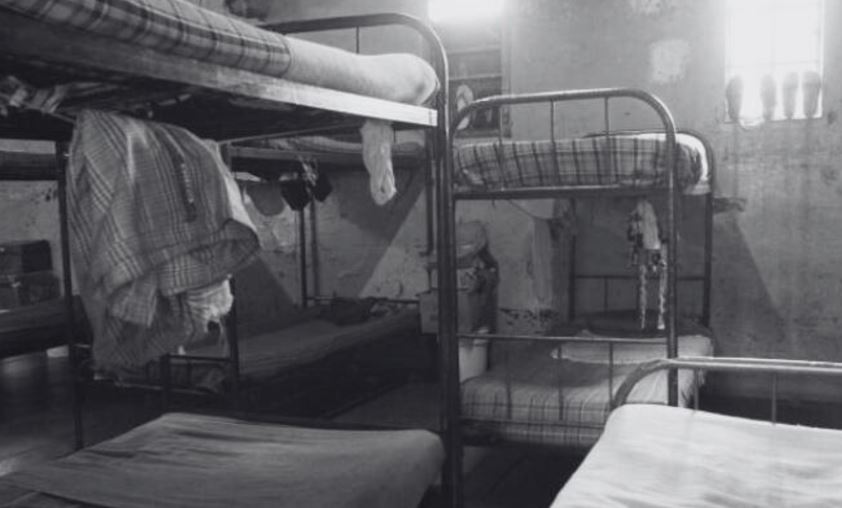

At the centre of this crisis is a distressing account from Senkoase High School. Teacher ’Mampho Mathaba revealed that when her students cannot afford or access sanitary pads, they tear pieces off the very mattresses they sleep on, using the foam and fabric as makeshift menstrual products.

This desperate act, deeply humiliating and unsafe, speaks to the severity of deprivation these girls face. A mattress, meant to provide rest and comfort, becomes a tool for basic survival. This underscores a crisis that threatens their health, dignity, and fundamental right to education.

While menstrual products are taken for granted in many developed countries, in rural and impoverished communities across Lesotho, the lack of access fuels what is known as “period poverty.”

Its effects ripple through every aspect of a girl’s life.

The most immediate and damaging consequence is on schooling. Without adequate materials to manage their periods hygienically and securely, girls miss classes, often staying home for the entire duration of their menstruation.

As Mathaba explained, this absenteeism is not always temporary. In the most tragic cases, girls never return to school, creating a persistent cycle of disadvantage that follows them into adulthood.

“Missing several days of school every month, sometimes up to a fifth of their instructional time, causes girls to fall behind their peers. Over time, this learning gap becomes impossible to bridge, leading many to drop out entirely and limiting their future job prospects and economic independence,” Mathaba said.

The Member of Parliament for Hloahloeng, Katleho Mabeleng, confirmed that this crisis is widespread. Mabeleng explained that in many remote areas, women and girls rely on torn pieces of old clothing or even blankets to manage their periods.

“Even when families manage to scrape together money for pads, the logistics alone, walking long distances to shops in rural areas, create an almost insurmountable barrier. Ultimately, poverty is the primary driver, turning a normal biological function into a catastrophic hurdle,” he said.

This is not merely a health or education issue; it is, as the World Bank Group emphasizes, a matter of human rights and dignity.

Globally, an estimated 500 million women and girls lack access to menstrual products and adequate facilities.

Effective Menstrual Health and Hygiene (MHH) requires three essential components: reliable water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities; affordable and adequate menstrual materials; and a supportive environment free of stigma.

When any of these elements is missing, the dignity and well-being of the girl child are compromised.

In Lesotho, the challenges faced by girls are further deepened by entrenched stigma and widespread misinformation. Menstruation is often surrounded by silence, shame, and harmful myths that isolate girls and discourage open discussion.

The newly launched national programme acknowledges that providing products alone is not enough. It integrates a strong educational component designed to dismantle these myths and build knowledge.

Mathaba welcomed this shift, noting that although sexuality education is part of the curriculum, the new programme, delivered by trained experts, will greatly enhance understanding.

“Importantly, the programme teaches both girls and boys about menstruation. For boys, this education clears up the widespread misconception that menstruation is linked to a girl becoming sexually active. By explaining that menstruation is a natural biological process, the initiative promotes respect for women and girls and helps create a more informed, supportive community,” she said.

According to ’Maseretse Ratiea, National Programme Analyst for Adolescents and Young People at UNFPA, the education element is essential. It includes teaching what menstruation is, how to maintain hygiene during periods, and also involves parents. The goal, she said, is that by the end of the pilot phase, communities will have a significantly stronger understanding of menstrual health and hygiene.

Ratiea explained that the National Programme on Menstrual Hygiene is a coordinated initiative between the Ministry of Gender, Youth and Social Development and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

The pilot phase is being implemented in the districts of Mokhotlong, Mafeteng, and Maseru over a one-year period, after which it will be handed over to the government for nationwide scale-up.

She said the distribution model was deliberately designed to maximise impact and prevent diversion of products. Every girl aged 10 to 19 receives disposable pads, regardless of whether she is in school, lives with parents, or not, ensuring that vulnerable and out-of-school adolescents are fully included. Women aged 20 to 24 receive reusable pads, an approach that is both cost-effective and environmentally sustainable.

To reduce the risk of pads being sold or used by others in the home, distribution is done quarterly. Although each eligible girl is entitled to 16 packets of pads per year, she only receives three packets every quarter.

“This staged delivery is a practical measure to ensure the products serve their intended purpose—keeping girls clean, healthy, and in school,” she said.

Ratiea added that UNFPA is initially handing over 4,900 packets of sanitary towels, enough to meet the annual needs of 2,275 girls.

She emphasised that the programme’s goals reach far beyond sanitation. Improved menstrual management, she said, means girls can attend school consistently, avoid feelings of hopelessness, and reduce the likelihood of early marriage or pregnancy driven by prolonged absence from school.

“By understanding the link between menstruation and reproduction, and by remaining in supportive learning environments, girls gain the foundation to become resilient and capable individuals who can shape their own futures,” she said.

UNFPA Representative John Mosoti issued a strong call for cultural change beginning at home.

“We do not discuss these issues within the family. We do not educate the boys, and sometimes we do not even educate the girls about these things,” he said. “Boys need to understand menstruation—they will marry these girls, be their friends, their fathers, their brothers.”

The Minister for Gender, Youth, and Social Development, Pitso Lesaoana, expressed deep appreciation for the government’s long-term commitment to the programme. He highlighted the political will and sustained effort required to launch an initiative of this scale, stressing that the government has a responsibility to address one of the most fundamental barriers to girl-child empowerment.

Summary

- In one of the starkest illustrations of deepening poverty in Lesotho, some schoolgirls are ripping apart the mattresses they sleep on to make improvised sanitary pads during their periods.

- While menstrual products are taken for granted in many developed countries, in rural and impoverished communities across Lesotho, the lack of access fuels what is known as “period poverty.

- By explaining that menstruation is a natural biological process, the initiative promotes respect for women and girls and helps create a more informed, supportive community,” she said.

Ntsoaki Motaung is an award-winning health journalist from Lesotho, specializing in community health stories with a focus on sexual and reproductive health and rights, as well as HIV. She has contributed to platforms like “Be in the KNOW,” highlighting issues such as the exclusion of people with disabilities from HIV prevention efforts in Lesotho.

In addition to her journalism, Ntsoaki serves as the Country Coordinator for the Regional Media Action Plan Support Network (REMAPSEN). She is also a 2023 CPHIA Journalism Fellow.