Mokitimi Tšosane

Introduction

14 June 2025 marks the first anniversary of the landmark Democratic Congress and Others v. Puseletso and Others decision in which the Court of Appeal of Lesotho recognised the applicability of the basic structure doctrine as an implicit substantive limitation to constitutional amendment power entrusted in parliament. Interestingly, the decision was handed down when the nation was struggling with the procedural aspects for undertaking the mega constitutional reforms aimed at transforming the constitution from top to bottom. At the same time, a wave of democratic recession and backsliding fuelled by populist rhetoric was in full swing globally and continues to date. To counter this wave, this essay borrows from and addresses Godel’s idea on whether there is a hidden flaw in the Constitution which when leveraged legitimately can result in a democracy being transformed into a dictatorship.

History has proven that despots opposed to democracy and the constitutions that implement its ideals, principles, precepts, doctrines, conventions and practices can become either heads of states or heads of governments in democratic states through democratic processes. A typical example is Adolf Hitler’s democratic ascend to power and the consequent transformation of Germany from a democracy to a dictatorship. In 1933, Germany was swept by a wave of stealth authoritarianism where existing democratic processes and mechanisms were used to erode democracy. State actors neglected their constitutional duty to protect democracy to contain the predatory political ambitions of Adolph Hitler. With this history, it is no surprise that Germany adopted the Basic Law (Constitution) with eternity clauses which comprise certain fundamental features of Germany democracy which can never be destroyed or emasculated, not even by parliament.

Authoritarian populism has given rise to debates on safeguarding democratic constitutions, their core values and features against volatile political shifts. In recent times, since the third wave of democratisation, democracy has been in a recession. Authoritarian populists have strategically blamed democracy for governance dysfunctions. With the populace convinced that democracy has failed, these authoritarian populists take advantage of the degeneration to hollow out democratic structures, subtly declaring “popular” wars on democracy and the constitutions that embody its ideals. The United States of America, a country which has promoted democracy around the globe, is also facing extreme populist ideologies from President Donald Trump. The threat posed by Trump’s populism is by far one of the greatest tests to American constitutional democracy’s resilience.

States like Hungary, Poland, Israel, and Brazil have also fallen victim to anti-democratic populists’ antics, intensifying the democratic decay process. What is evident, as noted by Dan Mafora, is that populists deride democratic institutions as elitist and oppressive, especially those with the potential to constrain their power. In order to achieve these anti-democratic agendas, tools of constitutional change may form part of the strategies to entrench their power. Formal amendment procedures may be deployed to erode, destroy, subvert and/or emasculate the basic features and values of the constitution that underlie the democratic order in phenomena termed abusive constitutionalism and clownstitutionalism.

The Kingdom of Lesotho has not been or may not be any immune to signs of democratic backsliding and populist rhetoric against its democratic governance. An interesting rhetoric to challenge the traditional and conventional foundations of democracy has been echoed by prominent political figures and others disillusioned by governance dysfunctions. The current mega constitutional reforms premised on a populist rhetoric that the constitution is the source of political instability and military interference in politics also present a live challenge to the basic structure, features and values of the democratic constitutional kingdom. Given these developments, the essay addresses whether Lesotho’s current democratic constitution can be transformed into an autocratic or authoritarian instrument through the constitutional amendment procedures. In other words, are there hidden flaws in the amendment procedure for Parliament to torture the democratic life out of the Constitution to create a dictatorship?

Judicial Review of Constitutional Amendments, Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments and the Basic Structure Doctrine

There is without question that Parliament has the authority to amend every section in the Constitution. However, Advocate Karabo Mohau Kings Counsel warned that while “constitutional amendment is indispensable to constitutional development but, like a double edged sword, the process is capable of either helping or hurting a country’s project to build a constitutional state.” In the words of Van der Westhuizen AJJA, “a democracy can democratically destroy itself following constitutional prescriptions, a constitution can be gutted.” (Sic)

High Court and Court of Appeal of Lesotho’s recognition that the Constitution of Lesotho has a basic structure, basic features and core values that cannot be undermined, destroyed, subverted or emasculated through the formal use of the amendment procedure is a positive development. It is a positive development, propounding that the constitution amendment procedures should not be used to advance the tyranny of the majority, authoritarian populism, and democratic backsliding. In other words, it avails substantive constitutional remedies to counter democratic subversion, abusive constitutionalism, abusive borrowing, and clownstitutionalism.

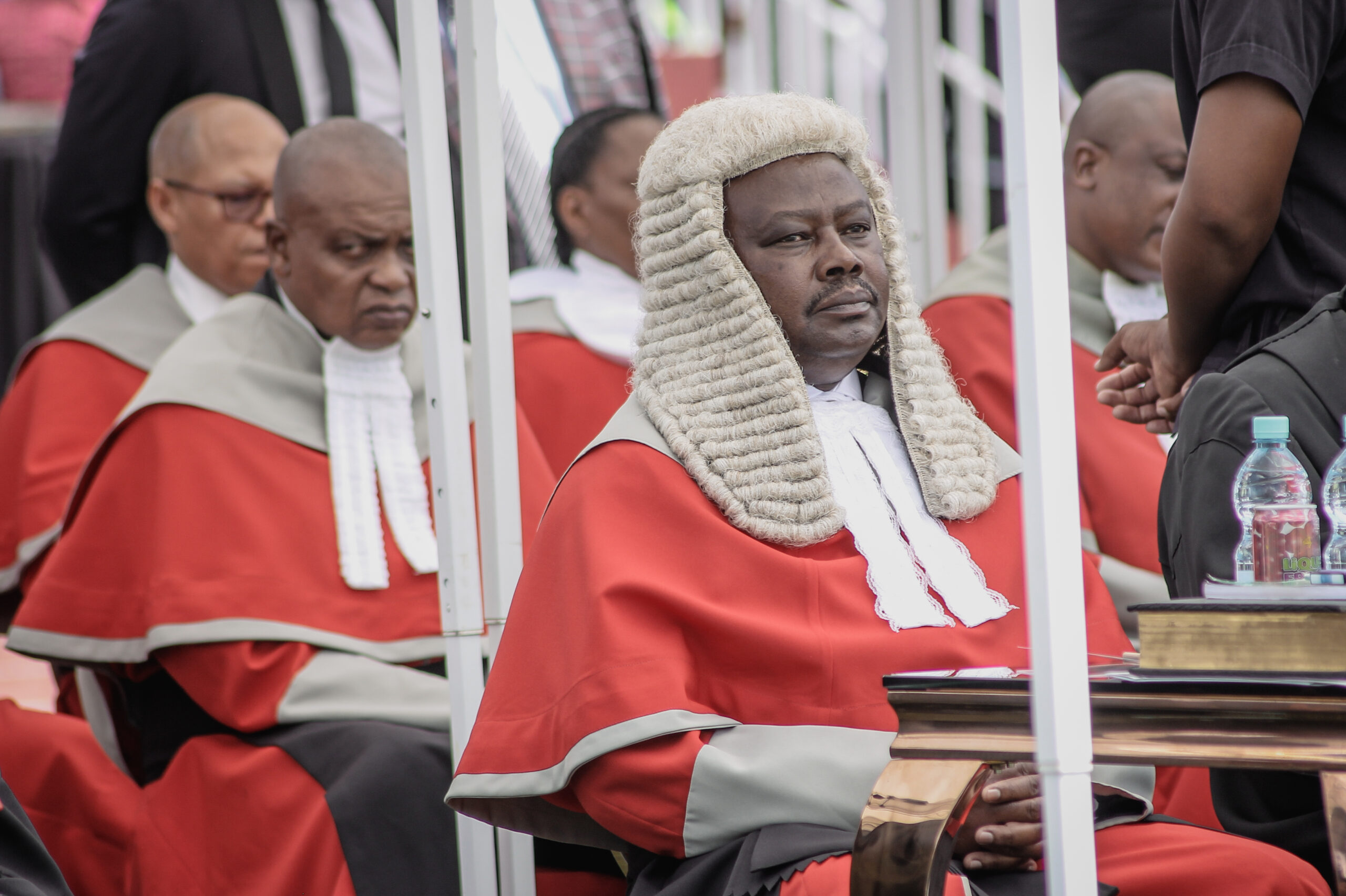

Musonda AJJA astutely highlighted that a constitution can be undermined through constitutional means, and the constitution should be insulated from opportunistic and radical amendments by limiting parliamentary sovereignty. In the end, amendment powers can pose an existential threat to the core tenets of constitutional order if left unchecked. Musonda AJJA observed further that “legislative power is intended to perfect imperfections in the constitution and not to make or remake the constitution.”

The rationale and purpose of the Basic Structure Doctrine, according to Musonda AJJA, is essentially to protect the constitutional democracy ideals, values and presuppositions from abuse through constitutional procedures. It is noted that with democracy undergoing a recession, constitutional amendment procedures may be used to undermine the very essence of constitutionalism. Musonda AJJA, in his concurring opinion, included the following rationales and purposes: maintains supremacy of the Constitution; upholds constitutional morality; preserves constitutional integrity; prevents authoritarianism; ensures stability and consistency; protects democracy; protects fundamental rights; and promotes judicial review.

Following a thorough analysis of some constitutional literature and judicial precedents, Mosito P highlights certain fundamental features of Lesotho’s Constitution, such as the separation of powers, the independence of the judiciary, and the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms, as forming part of the basic structure. Musonda AJJA, in his concurring opinion relying on Sikri C.J. in Kesavananda, added other foundational principles that constitute the basic structure: “the secular character of the Constitution, separation of powers between legislative, executive and the judiciary; the rule of law; independence of the judiciary; unity and integrity of the nation; judicial review; freedom and dignity of the individual; harmony and balance between fundamental rights and directive principles; the principle of equality; free and fair elections; independence of the judiciary; limited power to amend the Constitution; effective access to justice and principles (or essence) underlying fundamental rights.”

However, it is important to note that an exhaustive list of the foundational and core features upon which the constitution is built may not necessarily be unintelligible, as every section in the constitution has underlying principle(s). Damaseb AJJA drawing heavily from erudite submissions of Advocate M. Teele KC (for respondent) adds the exercise of the prerogative powers by the King and the uniqueness of the King in Lesotho’s constitutional democracy.

Writing for the minority of two out of five, Van der Westhuizen AJJA, indicated that at the core of the constitution of a constitutional democracy like that of Lesotho, is the principle, practice and ideal of democracy. MusondaA JJA, concurring opinion to the majority, declares that the Basic Structure Doctrine ensures that the Constitution remains intact while the Constitution keeps evolving through amendment. This is to guarantee that the Constitution keeps evolving through amendments. Musonda AJJA reasoned that the Basic Structure Doctrine ensures that the foundational principles of the Constitution remain intact while the Constitution keeps evolving through amendments.

The Court of Appeal noted that armed with this power of judicial review, the courts have exercised powers to protect the integrity and the spirit of the Constitution, having struck down amendments to the Constitution. To declare constitutional amendments unconstitutional, the courts have utilised explicit and implicit limitations on amendment powers. In the High Court, Moahloli J (retired) observed that “the Constitution has an implicit unamendable core that cannot be amended through delegated amendment powers…” In simple terms, the constitution amendment power cannot be used to destroy, subvert or erode the basic features, core values, and presuppositions that form the basic structure of the Constitution. Constitutional vulnerability to abusive constitutionalism, clownstitutionalism, constitutional dismemberment, constitutional capture, and constitutional retrogression through “amendment” procedures raises issues for judicial intervention to protect the fundamental principles of constitutionalism.

Rejection of Formalist Resistance to Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments

The minority judgement penned by J Van Der Westhuizen AJJA (Moses Chinhengo AJJA concurring) acknowledges the relevance and application of the Basic Structure Doctrine and those other formulations raised in the majority judgement. However, the learned judge raised the issue of the 3-year time lapse between the successful enactment of the Amendment to the Constitution and the constitutional challenge. In his words, “… the unreasonable lapse of three years since the passing of the Ninth Amendment Act, this seems like a situation in which courts neither have to, nor should, interfere.”

Perhaps, the idea that time cures unconstitutionality of otherwise unconstitutional constitutional amendments needs to be considered with a trajectory whereby obita dicta, Mokhesi J adopted a formalist resistance approach to unconstitutional constitutional amendments doctrine in Boloetse v Speaker of the National Assembly, 2023 (Boloetse II)and Christian Advocates and Ambassadors Association v Shao, 2022. In Boloetse II, this formalist resistance to the unconstitutional constitutional amendments approach was adopted by Mokhesi J and affirmed by J Van Der Westhuizen on appeal albeit obita dicta where he reasoned that if an Act of Parliament that amends the Constitution becomes law, the Court would then lack the necessary judicial authority to review its constitutional validity.

Arguing against formalist resistance to unconstitutional constitutional amendments, countries embracing constitutional supremacy, the courts serve as the bulwark to ensure that the laws passed by parliament are consistent with the provisions of the constitution. The supremacy of the Constitution, which the courts have to give effect to, is neither limited by time nor by compliance with the procedural dictates for passage of otherwise unconstitutional constitutional amendments. Courts declining or refusing to exercise judicial review over validity of unconstitutional amendments under the impression that time cures unconstitutionality or successful passage of amendments intended to undermine, emasculate, subvert, overthrow, destruct, overthrow or dismember the Constitution they purport to amend bars courts from reviewing constitutional amendments is court’s betrayal of the constitution. Lastly, the formalist resistance to unconstitutional constitutional amendments assumes that the derived secondary constituted powers to amend the constitution and the constituent power to change the constitution enjoy the same legal status as emphasised by Professor Yaniv Roznai in his writings.

At paragraph 109 of Pusetso Lejone v Speaker of the Assembly, His Lordship, Justice Keketso Moahloli points to the danger of formalist resistance to unconstitutional amendments by quoting Rosalind Dixon and David Landau in Transnational Constitutionalism and Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments. In the article, the two learned professors cautioned that amendment procedures may be used by a powerful president to extend their term in office, to remove parliamentary checks and balances on the executive power, and to narrow or suspend basic human rights protections. Therefore, the learned professors assert that recognising limitations on constitutional amendment powers has clear democratic benefits.

Conclusion

As with the actual proof to Fermat’s Last Theorem remaining a mystery, Godel’s Loophole, as told to a judge when Godel was sworn as a US citizen, remains a mystery. However, if this message could reach Godel, he should be assured that the Constitution of Lesotho has the safeguards, implicit and explicit, to protect its basic and core features from opportunistic amendments. However, it is important to note that an exhaustive list of the foundational and core features upon which the constitution is built may not necessarily be unintelligible, as every section in the constitution has underlying principle(s). In the same breath, it is worth noting that the basic structure doctrine and related appellations may not be a panacea against any form of authoritarian advances in a democratic state, but are an important guardrail. This does not necessarily mean that judicial abuse of the basic structure doctrine by the judiciary should be tolerated.

While complying with the procedure prescribed, parliament is not authorised to pass amendments engineered to defeat the very Constitution they seek to amend. The supremacy clause proscribes any exercise of power or authority in a manner that defeats the Constitution. In a judgement delivered on 2 May 2025, the President of the Court of Appeal in Molikuoa Sekhonyana and Anor v Principal Secretary – Ministry of Public Service and 4 Others notes that all exercise of public power must be rationally connected to the purpose for which the power was conferred. The amendment power as conferred was never rationally intended to be a gateway for the tyranny of the majority or designed as a tool for clownstitutionalists to undermine the Constitution.

The rejection of the formalist resistance to unconstitutional constitutional amendments is welcome as it exposes the Constitution to opportunistic and radical amendments, which may potentially lead to the tyranny of the popular elected political elites. In this populist era characterised by abusive constitutionalism, clownstitutionalism, and abusive borrowing, this would have created a fertile environment where a majority intoxicated with power may threaten the constitutional and democratic stability of the nation. In a country undergoing democratic recession due to democratic backsliding, powerful popular prime ministers with majorities in the National Assembly may “contrive a common mischief, to make nonsense of the Constitution”, to borrow Benson Tusasirwe’s words. When all is said and done, a constitution is not a self-executing document hence, it needs to be defended to defend the essence of constitutionalism, democracy, and the rule of law.

Professor Richard Albert argues that not every amendment is an amendment simply because it is called an amendment; others are dismemberments inconsistent with the values and presuppositions of the constitution they purport to amend. Adopting this proposition for substantive limitations to the constitution amendment procedure, the doctrine of unconstitutional constitutional amendment is a necessary feature of modern constitutionalism in Lesotho’s context. For various reasons, the doctrine seeks to protect the Constitution from radical, revolutionary amendments meant to defeat or make a joke out of the very Constitution they were meant to perfect.

Summary

- Puseletso and Others decision in which the Court of Appeal of Lesotho recognised the applicability of the basic structure doctrine as an implicit substantive limitation to constitutional amendment power entrusted in parliament.

- To counter this wave, this essay borrows from and addresses Godel’s idea on whether there is a hidden flaw in the Constitution which when leveraged legitimately can result in a democracy being transformed into a dictatorship.

- The current mega constitutional reforms premised on a populist rhetoric that the constitution is the source of political instability and military interference in politics also present a live challenge to the basic structure, features and values of the democratic constitutional kingdom.

Your Trusted Source for News and Insights in Lesotho!

At Newsday Media, we are passionate about delivering accurate, timely, and engaging news and multimedia content to our diverse audience. Founded with the vision of revolutionizing the media landscape in Lesotho, we have grown into a leading hybrid media company that blends traditional journalism with innovative digital platforms.