Nicole Tau

Children see the world through rose-coloured glasses, a view that helps them survive. Adults, in contrast, feel they belong to a different world—one where their purpose is to protect children, keep them safe, and nurture them as they grow.

But what happens when the very person entrusted to protect a child crosses that line, shattering their sense of safety before they even understand what is happening? Though they may not fully comprehend it, their bodies instinctively know it’s wrong, leaving them locked in confusion, shame, and a profound sense of insecurity.

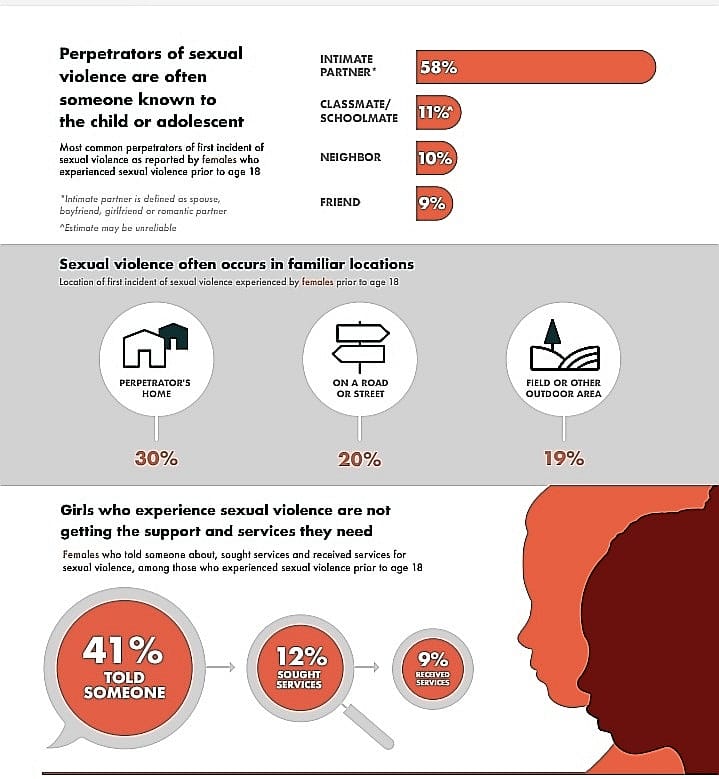

Every second, three girls and two boys somewhere in the world become victims of sexual violence. In the past year alone, that’s over 150 million children—82 million girls and 69 million boys—whose lives have been fractured by sexual abuse.

Even as headlines celebrate strides in gender equality and human rights, these deeply rooted violations persist worldwide, cutting across borders and cultures. For children in Lesotho, the reality is equally distressing: 15 percent of girls and 5 percent of boys experience some form of sexual violence before their 18th birthday.

These numbers reflect a global crisis and highlight how silence, stigma, and enduring legal and social barriers prevent millions from finding justice and healing.

Global Survey Spotlights Prevalence and Solutions

Together for Girls, a global partnership against child sexual violence, has taken on an ambitious mission: to pull back the curtain on an issue many still avoid. Through their Break the Record survey campaign, they have created a groundbreaking 2024 dataset that not only counts cases but tells a story of millions of lives affected in silence.

Through the Violence Against Children Surveys (VACS), conducted in partnership with the United Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), this data spans 193 countries, including Lesotho, and over 2 billion children.

It is a roadmap for change, built on voices from around the world, showing leaders the global scale and persistence of childhood abuse. For the first time, it gives them clear evidence and a way forward.

Are the cases on the rise? Yes, however, the vast majority of these cases have in the past gone unreported.

Daniela Ligiero, who is the CEO of Together for Girls and a survivor herself, explains: “The abuse has always been there — in homes, schools, and religious organisations. It has been underreported, but it has always been there in the shadows. It is only now, with more children coming forward and data collected from all corners of the globe, that the full picture of this crisis is coming to light.”

Ligiero was six years old when she was first abused by someone close to her family. Now, she is driven by a commitment to help others find justice and safety in their own communities.

Lesotho’s Cultural Barriers shape children’s reality

In Lesotho, victims face unique challenges. Cultural mindsets inhibit progress, as societal pressures often discourage young survivors from speaking out. Many families fear social repercussions, while traditional views hold a deep-rooted scepticism toward children’s accounts. This results in doubt, shame and even further abuse for children who do speak up.

Earlier this year, in June, a painful story circulated on the social media platform, Facebook, that brought a survivor’s experience into sharp focus. Now 27 years old, this young woman recounted an ordeal she endured at just 16.

“I was almost raped by my father. My heart bleeds. He was not someone who had ever kissed me, but suddenly he would kiss me, even forcing his tongue into my mouth. He did it once, then again. The third time, when he touched me, I ran,” she said.

The memories are vivid. She described how he would wait until she was alone, choosing his moments carefully, keeping away when other family members were nearby. But when she was left alone he would call her to his bedroom. The abuse escalated. “That is when I decided to speak out.”

Her first call was to her Mother, who was working in South Africa. She confided in her, hoping for safety or validation, but her mother, constrained by distance, encouraged her to tell a family elder. When she did, she was met with disbelief.

“My aunties, from my father’s side, accused me of lying and said that I was making it up to ruin their brother,” she recalled. “Even when I told another woman in the village, she only gathered us all – my father and my aunties – and warned me never to speak of it again.”

And with that, the young girl was silenced. Years later, she says she still carries the scars. “I am still hurting,” she said. “I ask myself every day if that man really could be my father.”

Once shared online, her story was met with a blend of sympathy and outrage, but also dismissiveness. Some social media users expressed sorrow and anger, others reacted with alarming indifference and even humour at her expense.

Image Credit: http://togetherforgirls.org/

Children’s Safety at Risk in Growing Online World

Ligiero highlighted that technology, while often viewed as a tool for progress, has unwittingly become a breeding ground for online abuse and exploitation.

“Right now, the burden falls heavily on parents to monitor their children’s online activities,” she says, emphasising the need for governments to create digital safety regulations.

One strategy, Ligiero suggests, is a “Safe by Design” model for technology companies, ensuring that any new app or social media platform is built with protections for young users. Without this, the unregulated digital sphere leaves vulnerable children at even greater risk of exploitation.

A child or caregiver might wonder: what are the warning signs to watch for, and how should they respond to suspected abusive behaviour? Fight Child Abuse, a global campaign for child abuse awareness and prevention, highlights some key red flags. These include isolating the child for excessive alone time, discouraging involvement from other adults, crossing personal boundaries, giving secretive gifts, and “accidentally” exposing the child to inappropriate content.

If someone suspects grooming or abuse by an adult, they are advised to document their observations and report their concerns to the authorities. Many organisations, such as child abuse hotlines, offer anonymous reporting options. Maintaining open communication with the child and seeking professional support are also crucial steps for protection and support.

Protection for Society’s Most Vulnerable is Key

Children with special needs are often among the most vulnerable, preyed upon by those who take advantage of their perceived helplessness. In a recent case, a 14 year-old-girl with a mental disability from the Botha-Bothe district was reportedly sexually assaulted by five men.

When she was taken to the hospital, it was discovered that she had HIV/AIDS.

While talking about these issues can be painful and often makes people uncomfortable, many survivors find that sharing their stories is also a step toward healing. It is a way to challenge communities to protect the most vulnerable among them and to break the silence that enables their suffering.

Adding to these challenges, Lesotho’s mountainous geography and limited resources further isolate rural communities, where healthcare, legal, and psychological services are scarce.

To address such issues, Ligiero’s organisation advocates for a survivor-centred approach, which she believes requires community engagement and strong local leadership.

“Breaking the culture of silence means involving everyone — teachers, parents, local authorities — to listen, believe, and act on behalf of children.”

Though rooted in the 2011 Children’s Protection and Welfare Act, Lesotho’s legal framework often fails to protect children effectively. In one case, at Semphetenyane, in Maseru, community frustration boiled over into mob justice when residents severely beat a man accused of assaulting a six-year-old girl.

The Women and Children Commission of Lesotho remarked in its October 2024 statement that such responses reflect widespread mistrust in the justice system. They called on law enforcement to establish rapid-response units and work with local Chiefs to uphold law and order.

A Global Call for Local Action

To bolster Lesotho’s response, groups like Together for Girls and the Brave Movement, a survivor-led international alliance, have called on the governments to establish “Survivor Councils.” These councils, composed of survivors and their advocates, aim to guide policy changes and ensure they align with real-world needs and experiences. In other countries, such as Kenya, this approach has already led to policy reforms, including the abolition of statutes of limitations for childhood abuse cases.

Additionally, Ligiero and her team emphasise a three-part framework for change, especially in under-resourced countries: prevention, healing, and justice.

Prevention begins in schools, with trained teachers equipped to detect abuse. Healing requires accessible mental health support; a 2023 study in Nature Medicine found survivors are at significantly higher risk for conditions like schizophrenia and conduct disorders. The final pillar, justice, calls for systemic reforms to hold abusers accountable and ensure survivors’ voices shape policy.

Ending childhood sexual violence requires a collective effort. In Lesotho, across Africa, and around the world, the call is clear: Listen to survivors. Protect the young. Address the systemic failures. And, most importantly, create a world where children can grow up free from the shadow of abuse. Only then can we hope to break this cycle of silence and shame, once and for all.

Ligiero shares a final message for survivors, especially young people who may feel isolated or unheard: “You are not alone. It is not your fault. Healing is a journey, and while you do not need to tell the whole world your story, know that there is power in your voice.”

Summary

- Through the Violence Against Children Surveys (VACS), conducted in partnership with the United Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), this data spans 193 countries, including Lesotho, and over 2 billion children.

- It is a roadmap for change, built on voices from around the world, showing leaders the global scale and persistence of childhood abuse.

- It is only now, with more children coming forward and data collected from all corners of the globe, that the full picture of this crisis is coming to light.

Your Trusted Source for News and Insights in Lesotho!

At Newsday Media, we are passionate about delivering accurate, timely, and engaging news and multimedia content to our diverse audience. Founded with the vision of revolutionizing the media landscape in Lesotho, we have grown into a leading hybrid media company that blends traditional journalism with innovative digital platforms.