Lesotho’s water wealth fails to quench its own people’s needs

Ntsoaki Motaung

Despite Lesotho’s vast water resources, many of its citizens remain thirsty, grappling with limited access to safe drinking water.

This paradox was put on the spotlight during the 6th SADC Groundwater Conference recently held in the country.

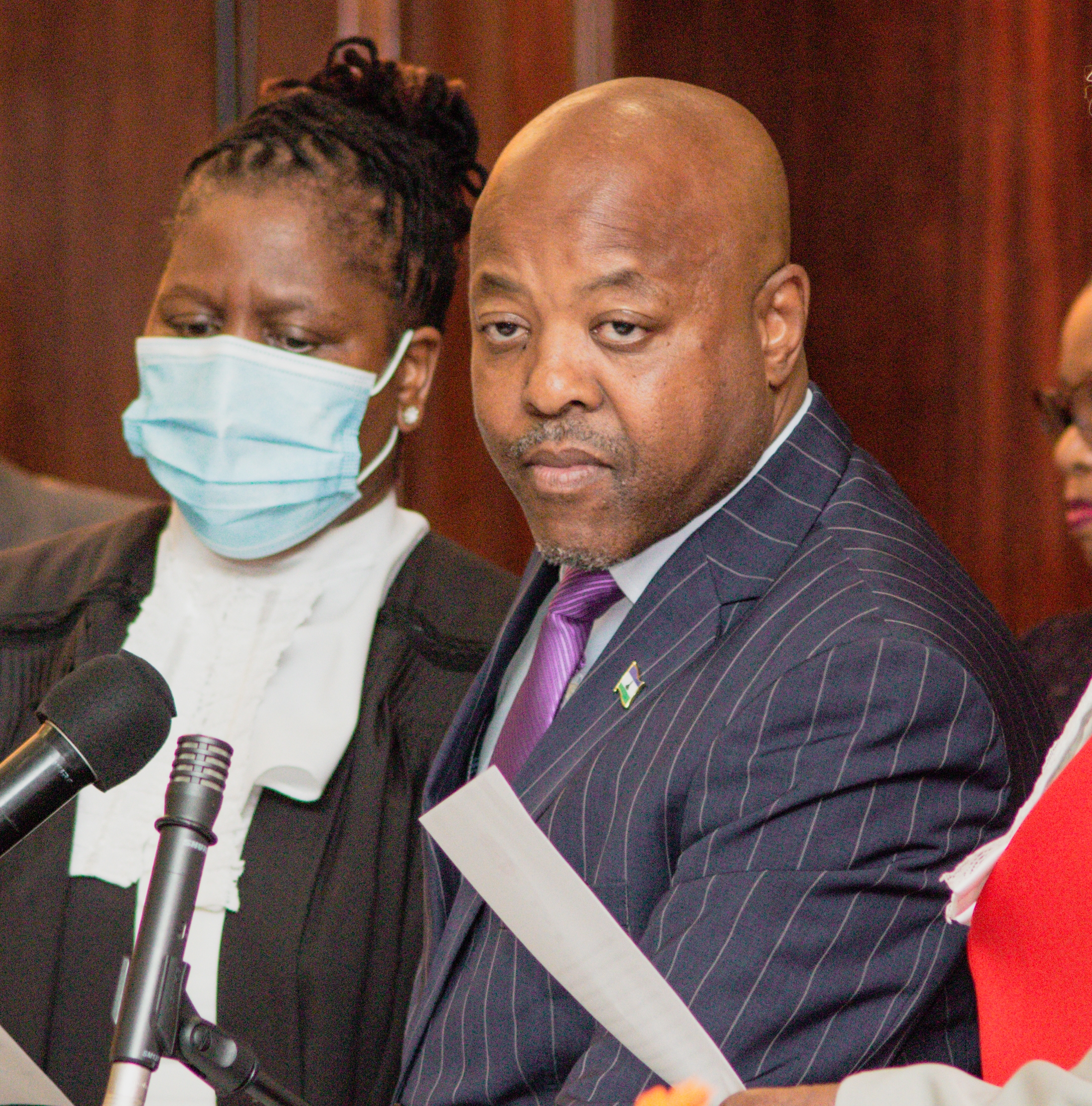

The Minister of Natural Resources, Mohlomi Moleko, praised Lesotho for its vast water resources during his speech at the conference.

Moleko highlighted Lesotho’s unique position as the “water tower” of the region, situated within the Orange-Senqu River Basin, which includes Botswana, Namibia, Lesotho, and South Africa.

He noted that despite Lesotho occupying only 30 percent of the landmass in the region, it provides 40 percent of the water.

The minister further explained that Lesotho was one of the most beautiful countries, known for its breathtaking views, snow in winter, skiing, fresh air, and spring water.

He emphasised that the government views water as a key driver of the country’s economic development.

The Minister provided an update on three major water-related projects.

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP), which supplies South Africa with approximately 760 million cubic meters of water annually, with phase two aiming to increase this to over 1 billion cubic meters per year.

The Lesotho-Botswana Water Transfer Project, with a feasibility study set to conclude within a year, expected to transfer water to Botswana through a 700-kilometer pipeline.

The Lesotho Lowlands Water Project, which aims to provide water to the lowland areas of Lesotho.

However, Moleko’s optimistic view of Lesotho’s water resources contrasts sharply with the difficulties many Basotho face in securing clean water for their households.

The Lesotho Multiple Indicator Survey 2018 paints a sobering picture: nearly 25 percent of the population lacks access to safe drinking water, with 17 percent of households still using unprotected sources.

Climate change has exacerbated the situation, with droughts and erratic rainfall patterns worsening water shortages. As a result, many Basotho must walk for hours to collect water, often from sources that are unsafe.

These challenges have serious implications for human development and poverty reduction in the country, as the inability to access safe drinking water and sanitation hinders progress in these areas.

During the conference, ‘Mapolao Mokoena, Director of Infrastructure at the SADC Secretariat, discussed the governing instruments for transboundary water management.

Mokoena highlighted the Shared Water Protocol of 2000 and the 2005 policy currently under review, which considers climate change impacts. She also mentioned a five-year strategic plan for water resources management and other protocols for agriculture.

“We do have a protocol on the Shared Water Process of 2000. It articulates, it also touches a little bit on the issues of groundwater. We also have a policy that was developed in 2005, which we are currently reviewing. We are reviewing it because we are taking into account issues of climate change,” she said.

“We do have other instruments because we are a service. We provide a service for agriculture. We also have protocols there. We have strategies and policies there,” she added.

James Sauramba, Executive Director of the SADC Groundwater Management Institute (GMI), emphasised the conference’s theme, which focused on using advanced technologies, harnessing data, and establishing innovative governance structures.

This year’s theme, inspired by World Water Week’s initiative, “Bridging Borders: Water for a Peaceful and Sustainable Future,” sought to encourage collaboration in water management to enhance peace and security across the region and beyond.

“We hope this theme inspires you to shape our discussions throughout the conference,” Sauramba concluded.

In March 2021, local journalists Sechaba Mokhethi and Pascalinah Kabi published an article titled Disease Stalks Villages as Lesotho Sells Water to South Africa, revealing a stark contrast between Lesotho’s vast water resources and the struggles of its people to access safe drinking water.

They highlighted that communities living near Lesotho’s two largest dams, Katse and Mohale, face a daily battle to obtain clean water, as the “white gold” they see flowing in these dams is being sold to neighbouring South Africa.

According to the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority (LHDA), which manages the water sales, Lesotho earned a total of 11.2 billion maloti (approximately $746 million) from 1996 to 2020 by selling 16,401.3 million cubic meters of clean water to South Africa.

In 2020 alone, Lesotho earned 1.03 billion maloti (around $69 million) for the sale of 780 million cubic meters of water.

However, despite the financial gains from these water sales, the local communities near the dams have seen little benefit.

The journalists revealed that these villages often suffer from diarrheal outbreaks, attributed to drinking contaminated water from unprotected wells.

In some cases, villagers have taken matters into their own hands, connecting their homes to existing LHDA water tanks. Yet, they allege, the government often takes credit for these grassroots efforts, without providing the necessary resources to improve the community’s access to clean water.

The struggle for water also has a significant social impact, particularly on women and girls, who bear the brunt of the daily water collection. The hours spent walking to and from unprotected water sources not only affect the health of these individuals but also hinder the education of students, who are forced to spend valuable time fetching water instead of attending school.

The article underscored the growing disparity between Lesotho’s water wealth and the lived reality of its rural communities, who continue to face severe water access challenges despite the country’s water exports to its much wealthier neighbour.

Summary

- He noted that despite Lesotho occupying only 30 percent of the landmass in the region, it provides 40 percent of the water.

- The Lesotho-Botswana Water Transfer Project, with a feasibility study set to conclude within a year, expected to transfer water to Botswana through a 700-kilometer pipeline.

- In March 2021, local journalists Sechaba Mokhethi and Pascalinah Kabi published an article titled Disease Stalks Villages as Lesotho Sells Water to South Africa, revealing a stark contrast between Lesotho’s vast water resources and the struggles of its people to access safe drinking water.

Your Trusted Source for News and Insights in Lesotho!

At Newsday Media, we are passionate about delivering accurate, timely, and engaging news and multimedia content to our diverse audience. Founded with the vision of revolutionizing the media landscape in Lesotho, we have grown into a leading hybrid media company that blends traditional journalism with innovative digital platforms.