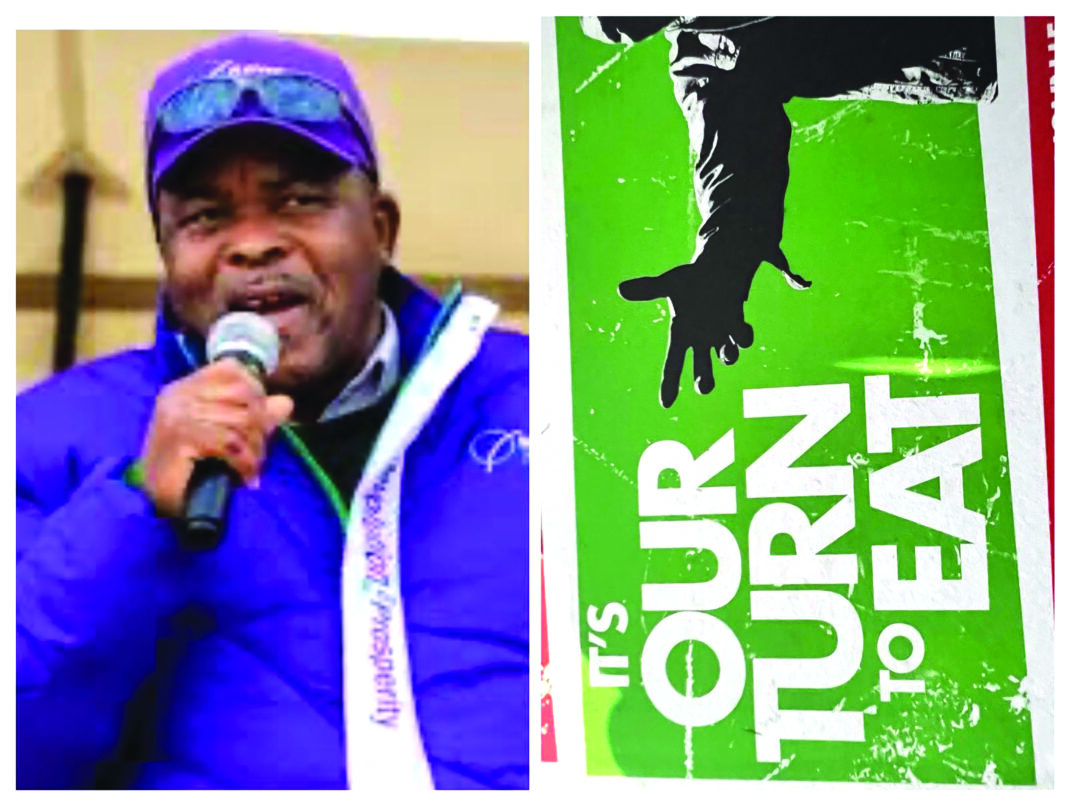

Chris Mokolatsie

Michela Wrong’s seminal book, It’s Our Turn to Eat, should be essential reading for Prime Minister Sam Matekane, his Ministers, and specifically Minister of Home Affairs, Lebona Lephema. Wrong, a seasoned British journalist with decades of experience reporting on Africa, documented the scourge of corruption in Kenya, especially in the aftermath of Daniel Arap Moi’s rule. More broadly, her book reflects on the persistent issue of political corruption across African nations—a problem that remains highly relevant in Lesotho under Matekane’s Revolution for Prosperity (RFP) party.

The recent hiring practices within Lesotho’s Ministry of Home Affairs and a supposed poverty reduction project, dubbed Lesupa-Tsela housed in the Prime Minister’s Office illustrate just how deep-seated corruption is within the RFP, exposing a disconcerting contradiction between the promises of change and the realities of governance. The nepotistic hiring of party loyalists at the Ministry of Home Affairs reveals how corruption continues to thrive, hidden in plain sight, under the guise of party loyalty.

A Political Earthquake Promising Reform

It wasn’t long ago that Lesotho’s political landscape was rocked by the emergence of Matekane’s RFP, a party that quickly garnered support by promising sweeping reforms and an end to corruption. Matekane, a prominent businessman, made bold promises, positioning his party as a clean alternative to the corruption-riddled administrations of the past. High on their list of promises was a commitment to stop public funds from being siphoned off by powerful elites, reform the public service to enhance accountability, and end the infamous “seoesooeso” practice—the appointment of party loyalists to public sector jobs.

Yet, the failure of RFP to secure a majority in the 2022 elections raised early doubts about Matekane’s capacity to fulfil these ambitious promises. Even with genuine intentions, could a new administration survive the temptations of incumbency, pressure from party loyalists, and demands for rewards from party members?

“Seoesooeso”: The Resilient Rot in Public Service

A particularly intractable issue in Lesotho’s politics is seoesooeso—a colloquial term describing the practice of securing government jobs for ruling party activists and supporters. Though Matekane’s government promised change, reports have surfaced alleging that hundreds of temporary staff were hired based on their political affiliations within the Ministry of Home Affairs. According to RFP Member of Parliament Moshe Makotoko, he was “seconded” by Minister Lebona to ensure only RFP-endorsed recruits were considered for these positions.

The irony is hard to miss: government officials, entrusted with the task of rooting out corruption, allegedly defy these values to engage in patronage politics. Instead of resisting seoesooeso, the RFP appears to have embraced it as a means to distribute benefits among loyalists, echoing the self-serving behaviour they once denounced.

Silence from the Top: The Complicity of Inaction

In the face of these allegations, the silence from Prime Minister Matekane the self-proclaimed “Mr. Clean” government is resounding. The lack of condemnation from the administration raises troubling questions. If the Prime Minister and his colleagues within the party truly seek to combat corruption, why hasn’t he spoken out? Why are there no suspensions and no investigation of those fingered within his party who are allegedly involved with unethical practices? Why are ministers involved in this shameless behaviour still in his cabinet?

The response, or lack thereof, reflects a disturbing tolerance for corrupt behaviour at high levels. Simply attributing these actions to rogue ministers and claiming ignorance of the issue would be disingenuous. The truth is that these appointments cannot happen without the Prime Minister’s tacit approval—or, at the very least, his willful disregard.

The Enduring “Turn to Eat” Mentality

These revelations make it difficult to see Matekane’s government as fundamentally different from its predecessors. Instead of a commitment to transparency and fair governance, RFP’s actions suggest they are perfecting the corrupt practices they were supposed to end. The same noxious atmosphere of seoesooeso, once condemned, has merely evolved to serve a new cohort of beneficiaries under Matekane’s leadership.

It is deeply troubling that, despite Lesotho’s long struggle for equitable governance, the political interest of those in power remains focused on who gets to eat rather than the country’s broader needs, especially the majority of unemployed youth. RFP’s supposed commitment to transparency and integrity has, so far, proven to be empty rhetoric. By tolerating and even enabling these practices, Matekane’s government shows little interest in creating a truly accountable government or offering hope for Lesotho’s future.

The Fundamental Question: Why Does Corruption Endure?

Ultimately, this situation raises important questions about corruption in African politics in general but in Lesotho specifically. Why is seoesooeso so hard to eradicate? Why do so many of our leaders in Lesotho including Prime Minister Matekane, reduce governance to the transactional politics of self-interest? Despite promising reform, Matekane’s administration now appears indistinguishable from previous regimes in its reluctance to uphold integrity and transparency.

The Prime Minister must recognise the opportunity he is missing to break this toxic cycle. To prioritize Lesotho’s future, Matekane must move beyond patronage and stand firmly against unethical conduct within his government. Only then can he hope to fulfil his promise of real change. ENDS.

Summary

- The recent hiring practices within Lesotho’s Ministry of Home Affairs and a supposed poverty reduction project, dubbed Lesupa-Tsela housed in the Prime Minister’s Office illustrate just how deep-seated corruption is within the RFP, exposing a disconcerting contradiction between the promises of change and the realities of governance.

- The nepotistic hiring of party loyalists at the Ministry of Home Affairs reveals how corruption continues to thrive, hidden in plain sight, under the guise of party loyalty.

- High on their list of promises was a commitment to stop public funds from being siphoned off by powerful elites, reform the public service to enhance accountability, and end the infamous “seoesooeso” practice—the appointment of party loyalists to public sector jobs.

Your Trusted Source for News and Insights in Lesotho!

At Newsday Media, we are passionate about delivering accurate, timely, and engaging news and multimedia content to our diverse audience. Founded with the vision of revolutionizing the media landscape in Lesotho, we have grown into a leading hybrid media company that blends traditional journalism with innovative digital platforms.