The trauma of 2008 is still clearly remembered by Limakatso Taolana. It was the year her life changed forever, not because of a slowly developing illness, but because of one horrifying moment.

After witnessing the body of her beloved grandmother, who had been brutally murdered in a ritual killing, Taolana’s body went into shock. She began experiencing seizures almost immediately. In an instant, she was no longer just a young girl. She was a patient living with epilepsy.

Her story stands at the centre of a broader struggle in Lesotho, highlighted during this year’s International Epilepsy Day. It shows that epilepsy is not only a medical condition but also a social battleground marked by stigma, misunderstanding, and an urgent need for systemic change.

For Taolana, the seizures were only half the battle. The social “seizures” – exclusion and name-calling – often hurt even more. During her school years, especially around 2012 when her condition worsened, she endured ridicule from those meant to protect her.

“My school days were the hardest because even the teachers stigmatised me and called me names like ‘mashoa a tsoha’,” she recalled.

The label filtered down to her classmates. She was excluded from games and school activities, treated as fragile and different. The isolation followed her into adulthood.

When she found love, she nearly walked away from it. She told her boyfriend they could not marry because of her condition. He refused to leave, and they eventually married, but the shadow of epilepsy lingered.

Even in her marital home, Taolana faced suspicion. When frequent seizures made it difficult for her to complete household chores, relatives accused her of pretending in order to avoid work.

At one point, she stopped taking her medication to prove she was not lazy or using her illness as an excuse to travel to town for check-ups. The decision was dangerous and nearly cost her life.

It was only after a frightening moment behind the wheel – when she managed to pull over seconds before a seizure struck – that she fully accepted her condition.

“I had to admit that there are things I will need to let pass me because of my condition,” she said.

Taolana’s experience is not unique. Nthabeleng Hlalele, founder of Epilepsy Lesotho, says stigma remains the main reason many Basotho avoid seeking medical help.

“Some may end up taking their own lives because they do not feel like part of the community,” Hlalele said.

The fear of being labeled or excluded keeps children out of classrooms and adults out of the workforce.

Official figures reflect only part of the reality. ’Malitaba Litaba, Head of the Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD) Division at the Ministry of Health, said approximately 5,000 epilepsy patients are registered in Lesotho. The true number is likely much higher due to limited diagnostic capacity.

“We lack MRI and CT scans to effectively do the work,” Litaba explained.

Without proper imaging tools, many cases are classified as idiopathic, meaning the cause is unknown. Although medication is available in Lesotho, accurate diagnosis remains a challenge, affecting the effectiveness of treatment.

Medical professionals are also examining cultural and environmental factors that may contribute to brain trauma. Dr. Mosiuoa Lesuhlo, an Officer Cadet from the Lesotho Defence Force (LDF), has recommended banning the traditional game known as ho kalla, noting that some head injuries linked to epilepsy result from the practice.

He also highlighted preventable causes in children, including birth complications such as oxygen deprivation during delivery and falls from elevated surfaces. Additionally, he called for clearer policies on driving licences for people living with epilepsy to enhance public safety.

Lesotho’s situation mirrors a wider global challenge. Dr. Lucy Mapota, representing the Office of the Director General of Health Services, said 15 million people worldwide are living with epilepsy and approximately 140,000 die each year.

However, hope remains. Dr. Sirak Hailu, Head of TB/HIV at the World Health Organisation (WHO), said while an estimated 50 million people globally live with epilepsy, up to 70 percent could live seizure-free with consistent access to affordable daily medication.

“Epilepsy is not contagious,” Dr. Hailu emphasised. “In most cases, it can be effectively managed at the primary health care level.”

However, in low-income countries such as Lesotho, nearly 80 percent of people with epilepsy live in areas where treatment gaps are significant, driven by a shortage of trained health workers and persistent myths.

Minister of Health Selibe Mochoboroane acknowledged that Lesotho has historically prioritised communicable diseases such as HIV and tuberculosis, often overlooking non-communicable diseases like epilepsy.

“The damage is now huge,” Mochoboroane said, noting that NCDs are now among the leading causes of death in the country.

He has called on the ministry to shift toward stronger scientific research to better understand the root causes of such diseases in Lesotho.

In response to global treatment gaps, the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and WHO have launched the Intersectoral Global Action Plan (IGAP), which sets ambitious 90-80-70 targets: 90 percent of people with epilepsy aware of their condition, 80 percent with access to affordable medication, and 70 percent of those treated achieving seizure control.

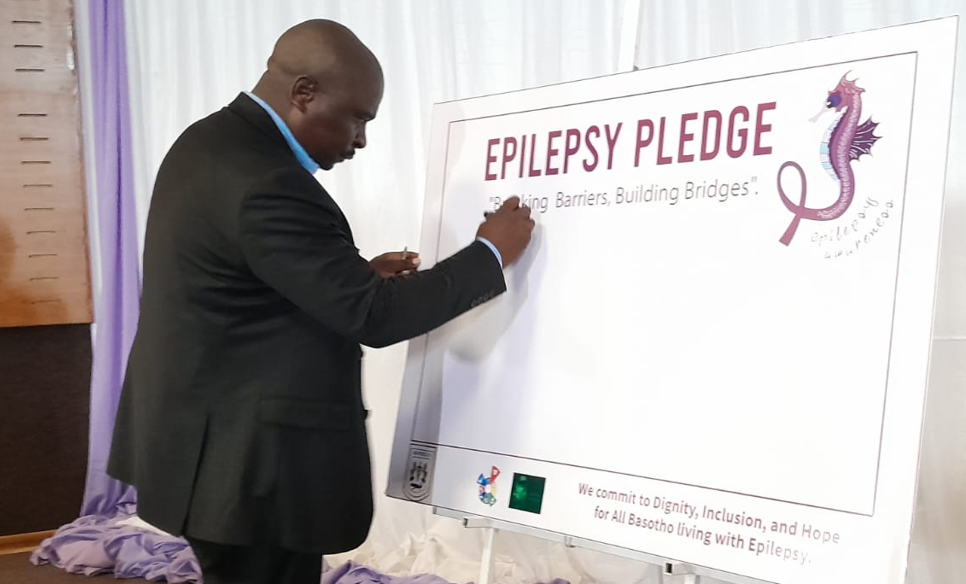

This year’s theme, “Epilepsy Pledge: Breaking Barriers, Building Bridges,” is a call to action.

For Taolana, that bridge means a society that offers employment instead of judgment, understanding instead of stigma, and medical support instead of myths.

Summary

- It shows that epilepsy is not only a medical condition but also a social battleground marked by stigma, misunderstanding, and an urgent need for systemic change.

- At one point, she stopped taking her medication to prove she was not lazy or using her illness as an excuse to travel to town for check-ups.

- It was only after a frightening moment behind the wheel – when she managed to pull over seconds before a seizure struck – that she fully accepted her condition.

Ntsoaki Motaung is an award-winning health journalist from Lesotho, specializing in community health stories with a focus on sexual and reproductive health and rights, as well as HIV. She has contributed to platforms like “Be in the KNOW,” highlighting issues such as the exclusion of people with disabilities from HIV prevention efforts in Lesotho.

In addition to her journalism, Ntsoaki serves as the Country Coordinator for the Regional Media Action Plan Support Network (REMAPSEN). She is also a 2023 CPHIA Journalism Fellow.