Kananelo Boloetse

I begin this op-ed with a frank acknowledgment: our constitution, like many others across the globe, is not without its deficiencies, some of which are indeed quite fundamental.

It is precisely for this reason that Basotho, in unison, have expressed the need for its reform. Notice my deliberate choice of the term “reform”—not amendment, not alteration, but reform. This distinction is critical and speaks to the collective intent of our people.

Despite its acknowledged weaknesses, I stand resolutely in defence of our constitution. My commitment to it is unwavering, for I believe that it remains a cornerstone of our democracy, deserving of rigorous defence whenever it is threatened.

However, when tasked with the responsibility of reforming the constitution, those entrusted with this mandate opted, for reasons best known to themselves, to pursue an approach centered on amending, rather than overhauling, the constitution.

Initially, I did not object to this strategy. My understanding of constitutional reform at that time was rudimentary compared to what I have since come to comprehend.

Thus, in 2022, an omnibus bill, comprising nearly 100 proposed amendments, was introduced and presented before Parliament. Regrettably, due to the habitual procrastination and lackadaisical attitude of our Members of Parliament (MPs), the term of that Parliament expired before the bill could be passed, leading to its dissolution.

In a controversial turn of events, a state of emergency was declared, ostensibly to facilitate the reconvening of Parliament to pass the omnibus bill.

It was at this juncture that I, alongside others who hold the rule of law in the highest regard, stood firm in our opposition. We could not, in good conscience, allow the constitution to be manipulated under the guise of expedient reform.

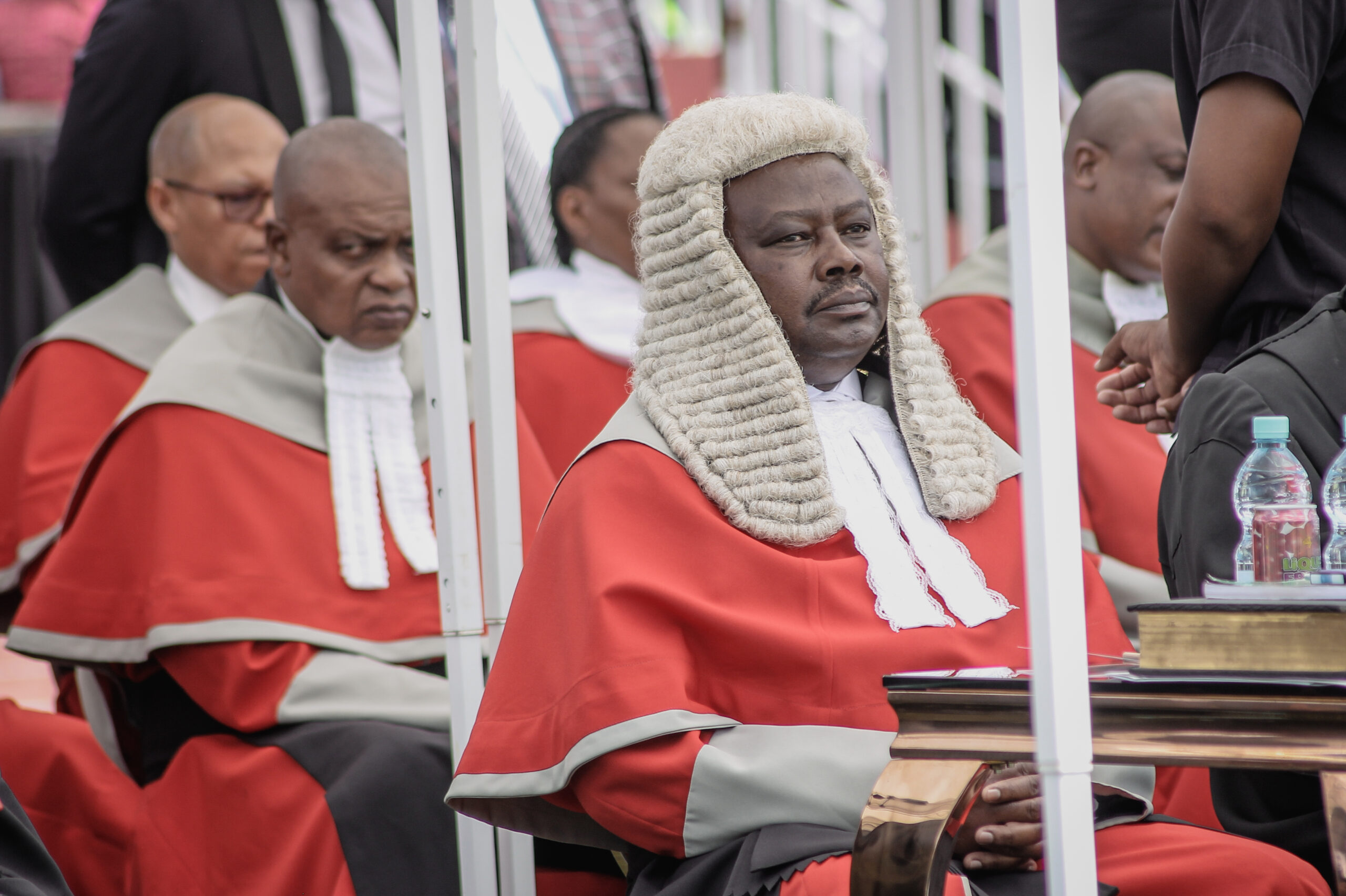

We challenged the declaration of the state of emergency and the reconvening of Parliament in court—and we prevailed. The case was straightforward, rooted in constitutional principles.

However, I did not anticipate the backlash that would ensue.

For merely upholding the constitution, we were branded as obstructionists, enemies of the reform process, and accused, without basis, of being beneficiaries of the status quo. To this, I ask: Does it appear that I have reaped any benefits from the mess our country is in?

On the contrary, I am a victim.

While I have acknowledged that our constitution has significant flaws that require redress, it is crucial to understand that these flaws are not the root cause of Lesotho’s persistent political instability and stagnation.

The crux of the issue lies with our political leaders, who lack a genuine commitment to constitutional democracy. They peruse the constitution not with the intent to uphold it, but to identify avenues for exploitation in pursuit of personal gain. This, more than anything, is Lesotho’s greatest challenge.

In this context, I am reminded of the renowned actor and comedian W.C. Fields, who was known for his atheism. Near the end of his life, Fields was found reading the Bible. When questioned, he quipped that he was “looking for loopholes.”

This is precisely what our leaders attempted to do in 2022. Having failed to pass the reforms through the proper channels, they sought refuge in a document they had long disregarded—the constitution—seizing upon a loophole that permitted the reconvening of a dissolved Parliament under a state of emergency.

The irony, of course, is that there was no genuine emergency to justify such a declaration.

Even now, I find it perplexing that those of us who opposed this constitutional manipulation were met with such animosity, while those who perpetrated it continued to sleep peacefully. It is a paradox that defies logic.

The impetus behind this hostility, I believe, lies in the external pressures from development partners who have heavily invested in the reform process. Their primary interest was in seeing the reforms completed, with little regard for the legality of the process. The rule of law, it seems, is only a priority when it aligns with their objectives.

The fallout from this legal challenge has been profound. It became evident that those displeased with our actions were intent on not merely defeating us but utterly destroying our credibility and reputation.

In 2023, when a new Parliament sought to revive the omnibus bill, we once again turned to the courts, arguing that such an action was unconstitutional. While the High Court disagreed, the Court of Appeal concurred with our position, affirming that once Parliament is dissolved, all pending business dies with it. Any attempt to resurrect it must begin anew.

This decision was met with even greater consternation from those who had already been aggrieved by our earlier victory. The development partners, who had poured resources into the reform process, were particularly incensed, fearing that their investments would be rendered futile.

In response, the omnibus bill was divided into three separate bills: one requiring a simple majority, one necessitating a two-thirds majority, and one demanding a referendum.

In May of this year, the first two bills—the 10th and 11th Amendments to the Constitution Bills—were presented in Parliament.

Yet, the situation in Parliament has devolved into what can only be described as chaos. Many critical details have been stripped from these bills, and MPs are now inserting their own amendments. This includes adding provisions to the 10th Amendment to the Constitution Bill that require a two-thirds majority to pass, even though this bill was initially designed for amendments needing only a simple majority.

In essence, it appears that MPs are, in effect, drafting a new constitution without the involvement of the true custodians of the Constitution—the people of Lesotho. This approach is nothing short of madness.

One of the fundamental purposes of having a constitution is to shield us from the dangers of majoritarian tyranny. It serves as a safeguard, not just against the excesses of the majority, but also against the possibility of MPs running amok and imposing their personal whims and wishes through constitutional amendments.

The constitution is designed to be the supreme law of the land, providing a stable framework within which the rule of law can prevail, and ensuring that any changes to this framework are made with the utmost care and respect for the principles of democracy and justice.

In this context, it becomes imperative that any attempts to amend the constitution are approached with caution, deliberation, and broad public consultation. The integrity of our legal system and the protection of our fundamental rights depend on it.

The constitution is not merely a tool for the powerful to reshape at will; it is a living document that reflects the collective will and values of the people. Therefore, it must be treated with the reverence and respect it deserves.

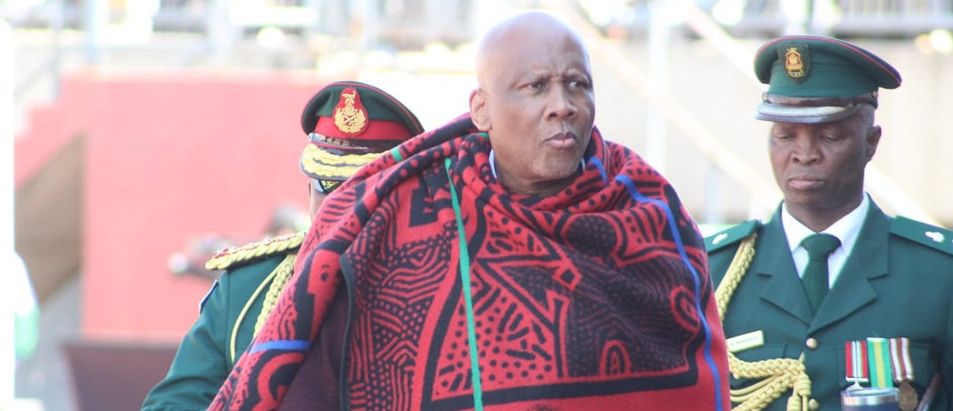

Lesotho stands as a unique democracy, where the King serves as the Head of State, embodying the unity and continuity of the nation.

The constitution, in its current form, delicately balances the roles of the King and the Prime Minister, with the Prime Minister serving at the King’s pleasure.

However, there are now efforts by MPs to alter this balance, proposing that the Prime Minister should serve at their discretion instead.

This shift not only undermines the existing constitutional framework but also threatens to diminish the role of the King in our Kingdom.

Some Basotho have expressed a desire to directly elect the Prime Minister. However, this idea was not included in the proposed amendments for a reason: Lesotho is a kingdom, and our system of governance is designed to respect and uphold the role of the King as Head of State.

To diminish the King’s role by placing the Prime Minister entirely at the mercy of Parliament is not just a significant departure from our traditions but a direct affront to the constitutional monarchy that defines our nation.

It is deeply concerning that MPs seek to reshape the governance of our Kingdom in this manner. What they propose not only disregards the importance of the King’s role but also risks destabilising the delicate balance of power that has served us well.

Yet, there is a deafening silence.

Those who might speak out are paralysed by fear, aware that any opposition to the current process could lead to being swiftly labeled as anti-reform and subsequently ostracised. They have witnessed what happened to those of us who dared to defend the constitution and are understandably reluctant to face similar consequences.

Meanwhile, our development partners are watching quietly from the sidelines. Their primary concern seems to be the passage of the bills, regardless of the final content or the satisfaction of the Basotho nation. Their focus is on achieving a result they can report as a success, regardless of the process that leads to it.

In this environment, any level-headed Mosotho who dares to speak reason to Parliament would likely be condemned for their efforts.

So, I now turn to you, Basotho, the rightful heirs of Morena Moshoeshoe’s kingdom. What should be our course of action?

Do we stand by as our constitution is altered without our consent, or do we assert our rights and demand a process that respects our voice and our democracy?

The future of our nation is in our hands, and the time to act is now.

We cannot, and will not, stand idly by as our King is reduced to a mere figurehead, stripped of his constitutional role and responsibilities.

As the nation, we must protect the integrity of our constitutional monarchy and ensure that any amendments to our constitution respect the foundational principles of our nation.

Summary

- My commitment to it is unwavering, for I believe that it remains a cornerstone of our democracy, deserving of rigorous defence whenever it is threatened.

- In a controversial turn of events, a state of emergency was declared, ostensibly to facilitate the reconvening of Parliament to pass the omnibus bill.

- Having failed to pass the reforms through the proper channels, they sought refuge in a document they had long disregarded—the constitution—seizing upon a loophole that permitted the reconvening of a dissolved Parliament under a state of emergency.

Your Trusted Source for News and Insights in Lesotho!

At Newsday Media, we are passionate about delivering accurate, timely, and engaging news and multimedia content to our diverse audience. Founded with the vision of revolutionizing the media landscape in Lesotho, we have grown into a leading hybrid media company that blends traditional journalism with innovative digital platforms.