“He stepped on my chest and neck… He said, ‘Because I love you’.”

- Mpho’s story sheds light on the painful reality of corporal punishment in Lesotho.

Nicole Tau

Winter mornings in Lesotho bite deep. That August day, the cold crept into 12-year-old *Mpho’s bones as he rose at 5:30 am, preparing for school like any other day. He boiled water for his bath, wolfed down a quick breakfast of homemade bread and Oros, of course, and set out into the morning chill, unaware that this day would mark a painful turning point in his young life.

As the 7th-grade class buzzed with early morning chatter, Mpho’s classmate taunted him, “Halala,” he teased. “You didn’t finish your notes. I wonder what Sir’s going to do to you…”

Mpho’s right hand still throbbed from a previous punishment, making it difficult to complete his notes, but he knew his classmate was right. The teacher’s wrath was unforgiving. He had every reason to worry.

When the teacher called for notebooks, Mpho, desperately, scribbled down as much as he could, hoping to escape attention, but it was no use. The teacher demanded Mpho bring him his notes.

Trembling, Mpho walked to the front of the class. The teacher compared his incomplete work with another student’s and then called Mpho to follow him.

Quietly, the teacher led him to the computer lab where grade one students were busy with their lesson, now watching.

“He asked me to bend down and hold a metal rod-like object on the floor,” Mpho said.

Mpho hesitated. The rod was too low. Instead, he reached for the wall, but the teacher barked at him again. Reluctantly, Mpho bent down and grasped the rod. The two blows came quick and sharp, the red hosepipe stinging his back. He yelped in pain, pleading for mercy, but it only fueled the teacher’s fury.

“He demanded that I put my head between his thighs,” said Mpho.

Mpho refused, gripping the wall, until two slaps landed on his face, forcing him to comply. Humiliated, he crouched between the teacher’s thighs, trying to breathe through the panic. But that was not enough, as he pushed Mpho down on the floor and whipped him again across his buttocks.

The teacher then forced him to the floor, pinning him down with his shoe, and pressing hard on Mpho’s neck and chest.

With other students out at lunch, the teacher remained, standing over Mpho like a shadow. He picked up the stick again, and asked, “Do you know why I’m doing this?”

“No, sir,” Mpho whispered.

“It’s because I love you. If I didn’t love you, I wouldn’t do this.”

The twisted words hung heavy in the air as the teacher ordered Mpho to crouch between his legs once more. But this time, something in Mpho snapped. When the teacher reached for the hosepipe, Mpho wrenched free, grabbed the pipe, and hurled it toward the chalkboard. His defiance earned him two sharp slaps across the face, and just like that, the fight drained out of him.

Falling to his knees, Mpho waited for the next strike, for the blows to rain down, but they never came. The teacher, seemingly satisfied with his domination, left him alone

“Our children are our greatest treasure. They are our future. Those who abuse them tear at the fabric of our society and weaken our nation.” – Nelson Mandela.

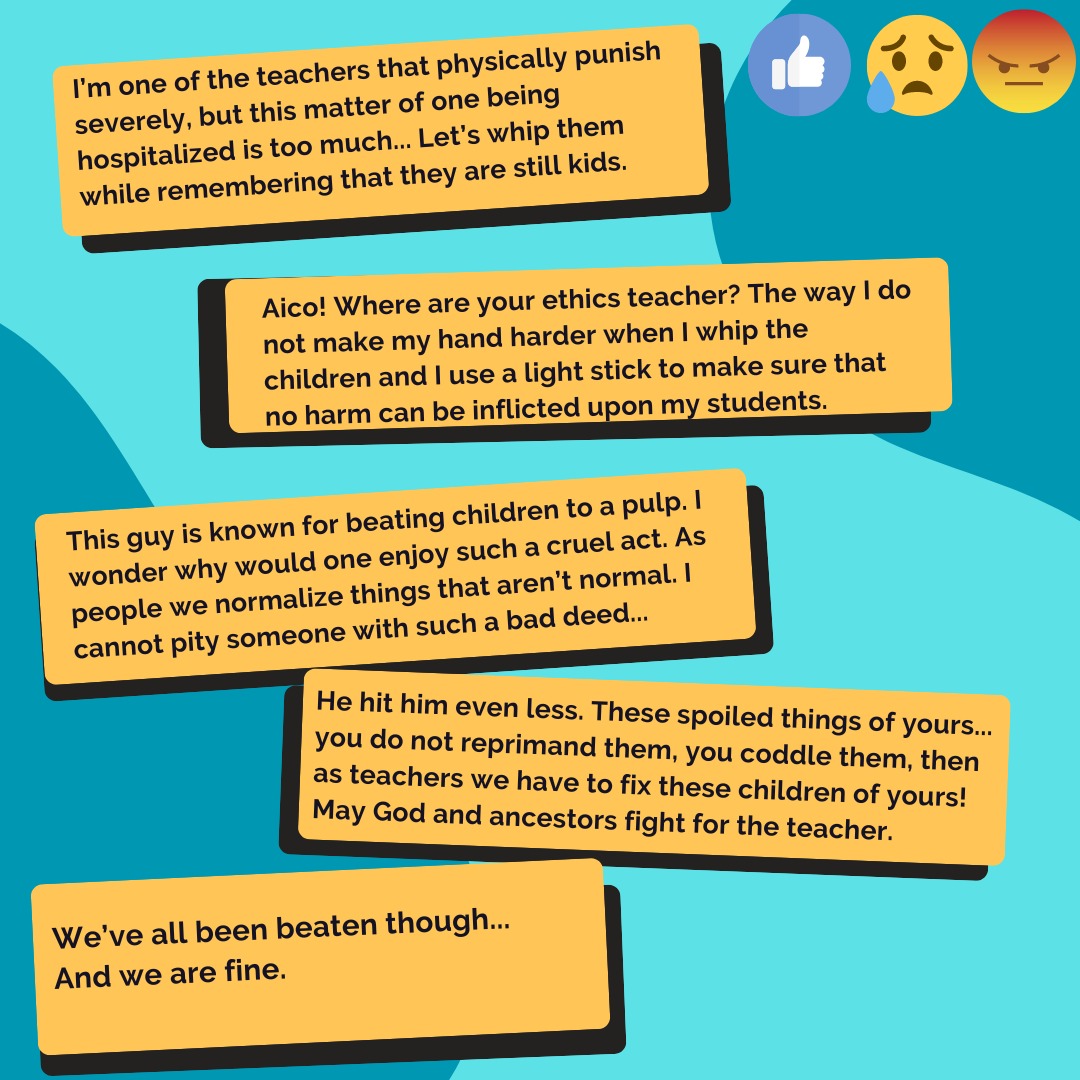

When the incident reached social media, headlines focused on the teacher. However, public reactions revealed deeper divides in attitudes toward corporal punishment.

A post titled “Look at the Teacher that Assaulted the Child” generated over 200 comments, with most condemning the abuse. Some called for the teacher’s dismissal, with one commenter writing, “I think the teacher should be behind bars… or he will kill children.”

While 84 percent of comments condemned the teacher, calling for dismissal, a small but vocal 16 percent sympathised, suggesting mental health issues or blaming the child.

Even among those critical of the teacher, many still supported corporal punishment in general, only drawing a line between discipline and outright abuse.

Reports from parents and former students revealed that this teacher’s behaviour was not an isolated incident, revealing a culture of silence and complicity in schools where such violent outbursts had long been ignored.

“The child is not a vessel to be filled, but a flame to be ignited.” – Maria Montessori.

A 2024 UNICEF survey revealed that 76 percent of children aged 1-14 in Lesotho have experienced violent discipline, including physical punishment or psychological aggression.

Despite Lesotho having ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1992) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (1999), which mandate protection from all forms of violence, corporal punishment remains entrenched in schools, defended as a cultural norm.

After the brutal beating, Mpho was forced to sit through the rest of the school day in excruciating pain. His suffering went unnoticed, or worse, ignored. By the time the final bell rang, he could barely carry his school bag. His hour-long walk home stretched even longer as he walked under the weight of his injuries.

His mother, *‘Maneo, noticed the lash marks running down his back to his buttocks.

“The teacher had beaten him so badly,” she said, her voice trembling. “I didn’t know what I was supposed to do.”

When Mpho complained of chest pain and difficulty walking the following day, ‘Maneo rushed him to the hospital, where shocked nurses immediately called doctors to assess the severity of his injuries. Mpho was admitted for monitoring, placed on a drip, and fitted with a catheter.

“The most important thing we can do is instill in our children a sense of hope and possibility.” – Michelle Obama.

Psychotherapist ‘Makamohelo Malimabe explains that corporal punishment can have lasting effects on a child’s brain development.

During critical developmental years, children may normalise such abuse, internalising violence as part of their reality.

“Corporal punishment and physical abuse are two sides of the same coin,” Malimabe says. “No matter the intention behind it, the harm is the same.”

She challenges the cultural defence of corporal punishment, drawing a powerful comparison to domestic abuse.

“If a spouse slapped their partner, we’d call it abuse. So why, when a teacher beats a child for being late, is it called corporal punishment?”

Malimabe argues that terms like “corporal punishment” soften the harshness of the act, making it harder to grasp the real harm.

“We need to stop calling it ‘corporal punishment’ and start calling it what it really is, violence. Adults are taking out their frustrations on defenceless children.”

“I raise my voice not so that I can shout, but so that those without a voice can be heard.” – Malala Yousafzai.

Lesotho’s legal community is growing increasingly concerned about the gap between law and practice when it comes to corporal punishment.

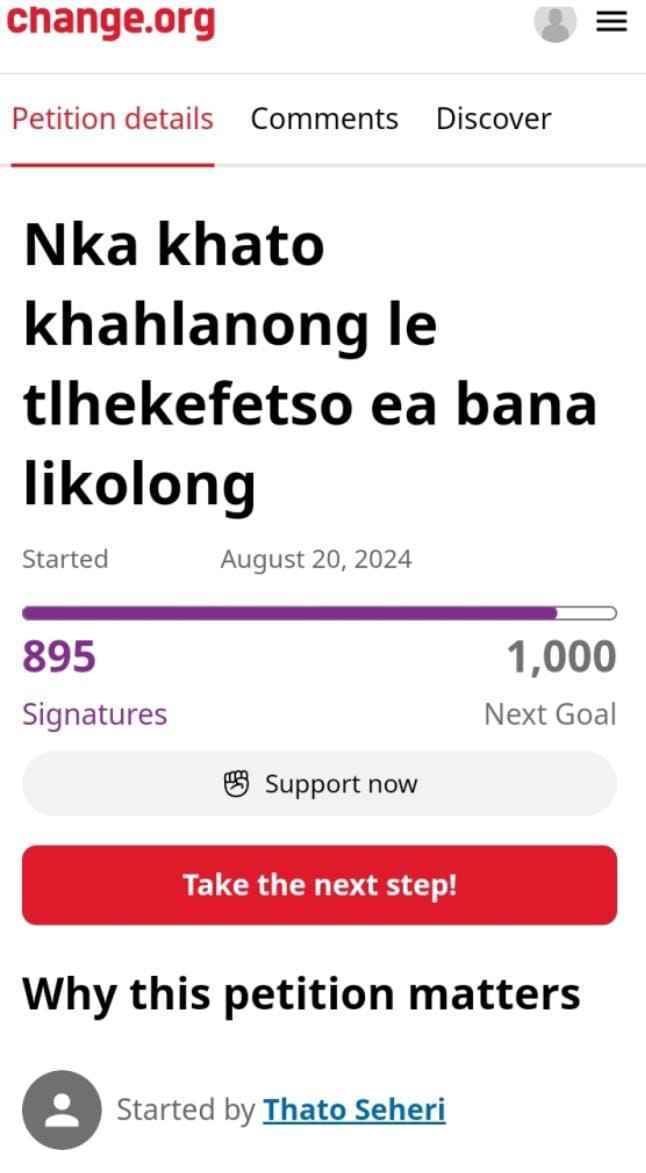

Advocate Thato Seheri, a human rights lawyer, points out that the Education Act of 2010 and the Children’s Protection and Welfare Act (CPW) 2011 remain vague on the issue, leading to widespread confusion.

“The law is silent on corporal punishment, so people interpret it in various ways. We need a clear court directive to establish whether it’s prohibited or not,” advocate Seheri says.

A local prosecutor echoes this sentiment, explaining that the courts are left to interpret what constitutes “reasonable chastisement.”

“It can be argued both ways, and the best argument wins… The burden falls on the shoulders of the courts to interpret what the reasonable chastisement is.”

The prosecutor also wishes parents would file civil claims against teachers who assault their children.

“In criminal cases, even if the teacher is fined, the money goes to the government, not the victims. In civil matters, families can claim compensation for the emotional and physical damage they’ve endured.”

Advocate Seheri stresses that the solution begins with a clear legal prohibition of corporal punishment.

The Ministry of Education and Training seems disconnected from the ongoing reality of corporal punishment in schools.

Principal Secretary Ratšiu Majara, however, offers a progressive stance, advocating for a shift in how children are disciplined.

“We need to engage students when they perform poorly, not beat them,” he said. Majara believes the ministry must focus on sensitising parents to non-violent forms of discipline and holding schools accountable for teacher behaviour.

Parents’ stories highlight systemic issues. Most only report corporal punishment when their children suffer visible injuries, and many cases stall at the police station. Some families, lacking funds, cannot even gather proper documentation, while others face delays in the courts, with cases dragging on for months or even years.

In Mpho’s case, the teacher charged with assault was released on bail for M1,500. The case, which began in August, is not set to proceed until 2025. Although the teacher eventually resigned, most teachers in similar cases remain in their positions.

Human rights bodies have repeatedly called for action, including the Committee on the Rights of the Child in its 2018 report. While corporal punishment is banned in Lesotho’s schools, the Committee urged the government to explicitly prohibit corporal punishment in all environments and establish safe reporting mechanisms for children.

The Committee also recommended training programs for parents and teachers to promote non-violent discipline, along with public awareness campaigns to shift societal attitudes.

Advocate Seheri concludes with a call for stronger punishment for those found guilty of corporal punishment.

“The penalties should be severe enough to send a clear message that corporal punishment is indeed prohibited.”

*The child’s name has been changed to protect their privacy.

This story was produced with the support of Media Monitoring Africa as part of Isu Elihle Awards.

Summary

- He boiled water for his bath, wolfed down a quick breakfast of homemade bread and Oros, of course, and set out into the morning chill, unaware that this day would mark a painful turning point in his young life.

- The twisted words hung heavy in the air as the teacher ordered Mpho to crouch between his legs once more.

- When the teacher reached for the hosepipe, Mpho wrenched free, grabbed the pipe, and hurled it toward the chalkboard.

Your Trusted Source for News and Insights in Lesotho!

At Newsday Media, we are passionate about delivering accurate, timely, and engaging news and multimedia content to our diverse audience. Founded with the vision of revolutionizing the media landscape in Lesotho, we have grown into a leading hybrid media company that blends traditional journalism with innovative digital platforms.