… insourcing criticised for allegedly violating mining laws and policies

Staff Reporters

Letšeng diamond mine’s recent decision to cut ties with Matekane Mining Investment Company (MMIC) and opt for insourcing mining activities has sparked a furious debate, with allegations swirling that the move runs contrary to crucial mining laws and policies promoting local involvement in the sector.

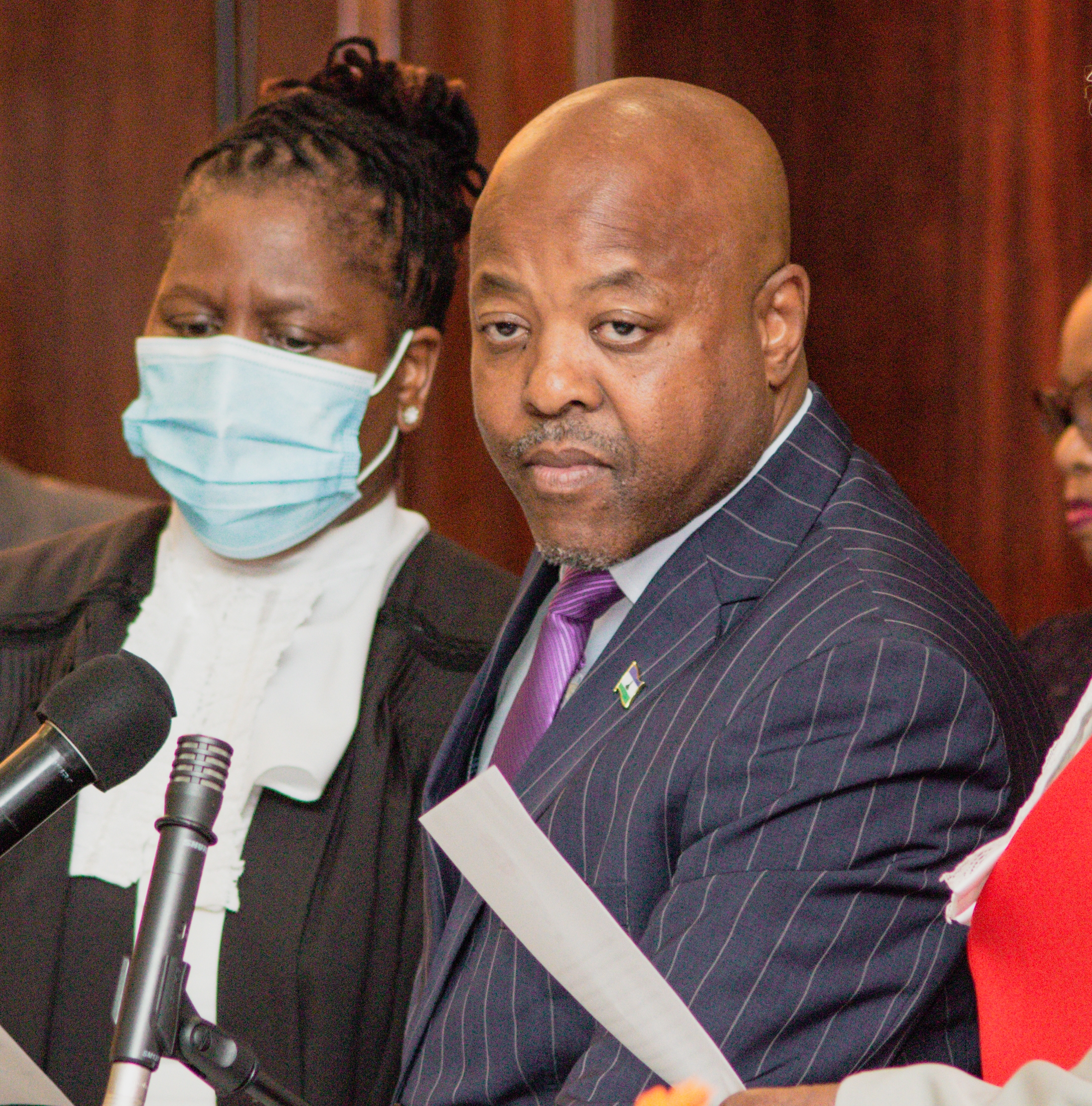

In an interview with Newsday yesterday, Machesetsa Mofomobe, the Basotho National Party (BNP) leader, vehemently criticised Letšeng’s decision, citing violations of mining legislation like the Mines and Minerals Act of 2005 and Mining Policy of 2015.

Mofomobe lambasted the move, asserting that it contradicts the Act and Policy’s spirit, which aims to empower local enterprises in mining operations.

He indicated that he believes that Letšeng’s insourcing resolution could spell doom for local enterprises in the mining sector.

Letšeng recently announced it is partying ways with Matekane Mining Investment Company MMIC after 23 years of partnership, and will be insourcing its mining activities going forward.

MMIC has been the provider of load and haul services at the mine, which is majority-owned by London Stock Exchange-listed Gem Diamonds, while the government of Lesotho holds the remaining 30 percent shareholding.

The unprecedented move by Letšeng to separate with MMIC – a politically exposed company owned by Prime Minister Samuel Matekane – sought to pre-empt a parliamentary motion to stop members of parliament from doing business with the state.

“The insourcing move by Letšeng violates the Mines and Minerals Act of 2005, which directs that where there is capacity; local firms must be preferred over foreign companies. The spirit of that Act was to empower locals, and that is in sharp contrast to what Letšeng is doing,” Mofomobe said.

“It has always been every government’s wish to increase local participation in key sectors of the economy, and it is disappointing to see the opposite happening from right under the Prime Minister’s nose, the highest ranking custodian of the country’s laws,” he added.

Mofomobe also alleged that Prime Minister Matekane became wealthy by benefiting from the very law that he today seems to let Letšeng undermine.

He said: “Since he worked closely with Letšeng, I expected the Prime Minister to ensure that his company would be replaced by another local company in Letšeng mine to preserve the empowerment of locals in the sector.”

The move by Letšeng also drew fire for seemingly disregarding the Minerals and Mining Policy of 2015, which underscores the need to domesticate mining industry jobs, empowering Basotho and bolstering their role in a sector currently dominated by foreign-owned companies.

Under its domestic empowerment section, the policy has a candid strategy to increase the usage of locally-owned and indigenous mining service providers in the mining sector, and “maximise the procurement of goods and services from local sources by giving preference to Basotho suppliers.”

Former Minister of Mining, Lebohang Thotanyana, who led the development of the policy, also questioned the implications of shutting out MMIC without opening doors for other local contractors.

Thotanyana cautioned against a domino effect, warning that such a move might strip Basotho enterprises of lucrative opportunities across the mining sector.

“What are the implications of this approach to local contractors? If MMIC has challenges of continuing why can’t it be released so that other local contractors can come in?”

He further said the move could have far-reaching industry-wide consequences where other mines could follow suit, leading to Basotho enterprises losing lucrative business in the process.

“Others might see it in the context of a perceived conflict of interest in the case of the PM but this has far-reaching consequences for the country and its private sector. It should be seen beyond just one man.

“The PM’s company can exit, but that does not mean all local contractors should be barred from the work. This is the only sector which has shown the potential to empower locals,” Thotanyana said.

Section 2, a local activist group, last week demanded Letšeng to unveil the financial intricacies surrounding its acquisition of assets from MMIC.

The demand was articulated in a robust statement released on Thursday which underscored the public’s unequivocal right to this information, citing its paramount importance in fostering accountability and nurturing trust in governance.

The activist group’s call extended further, urging Letšeng to openly disclose any sum designated as a “golden handshake” to MMIC due to the abrupt termination of their contract—concluded eleven months ahead of the stipulated schedule.

“This transparency is non-negotiable and crucial for fostering a culture of ethical business practices,” the statement read.

The group said it staunchly advocates for a society rooted in transparency, accountability, and unwavering ethical standards.

It emphasised Letšeng’s role as a torchbearer for these values, setting an exemplar for others to emulate.

However, Letšeng unequivocally rejected Section 2’s demand, stating: “The agreement between Letšeng and MMIC is protected by confidentiality clauses, as is customary in such transactions. Therefore, we are unable to disclose the terms of this agreement.”

The company also refused to divulge whether any sum was designated as a “golden handshake” to MMIC.

Summary

- “It has always been every government’s wish to increase local participation in key sectors of the economy, and it is disappointing to see the opposite happening from right under the Prime Minister’s nose, the highest ranking custodian of the country’s laws,” he added.

- “Since he worked closely with Letšeng, I expected the Prime Minister to ensure that his company would be replaced by another local company in Letšeng mine to preserve the empowerment of locals in the sector.

- Under its domestic empowerment section, the policy has a candid strategy to increase the usage of locally-owned and indigenous mining service providers in the mining sector, and “maximise the procurement of goods and services from local sources by giving preference to Basotho suppliers.

Your Trusted Source for News and Insights in Lesotho!

At Newsday Media, we are passionate about delivering accurate, timely, and engaging news and multimedia content to our diverse audience. Founded with the vision of revolutionizing the media landscape in Lesotho, we have grown into a leading hybrid media company that blends traditional journalism with innovative digital platforms.