Staff Reporter

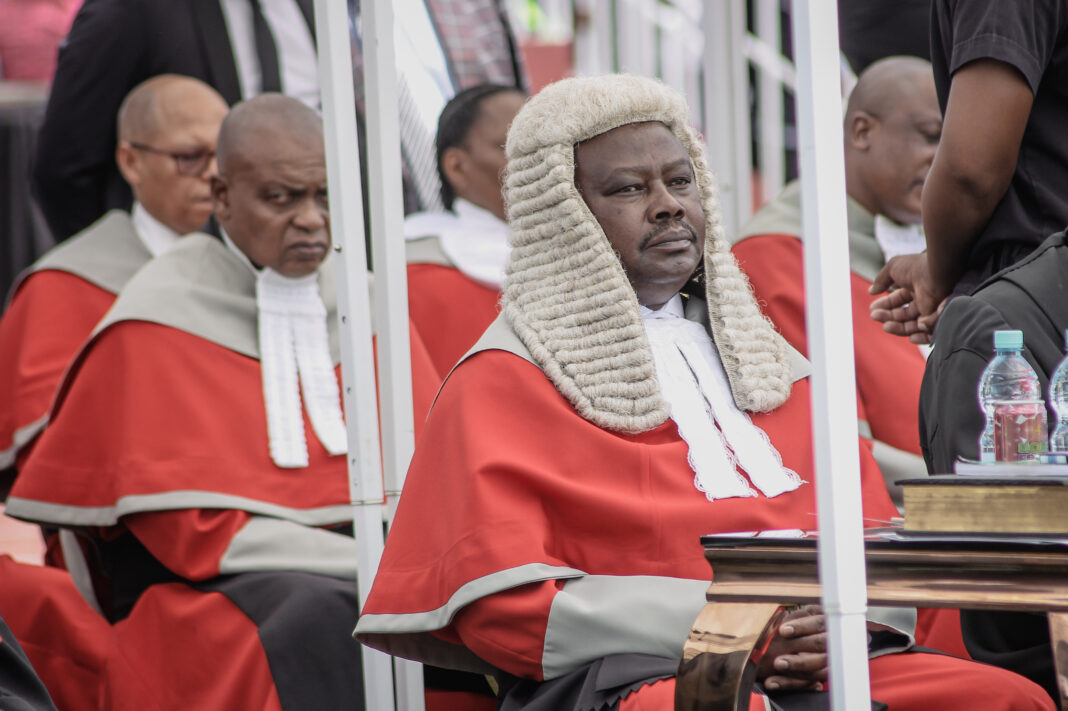

Chief Justice Sakoane Sakoane did not mince words when addressing the fate of the Amendment to the Constitution Bill, also known as the Omnibus Bill, referring to it as defunct and consigned to the history books.

“The amendment you are talking about now, which is now dead, I did not want us to talk about a dead thing, I wanted us to talk about where we are going,” Sakoane remarked during his recent speech.

He expressed strong skepticism about the effectiveness of the bill, stating: “But that Bill, which we now know has been consigned to the scrapyard of history, would never deliver what Plenary II wants. It was not even designed to do that because if you look at NRA (the National Reforms Authority), the membership of NRA was politically dominated. That was already flawed.”

These statements were part of Sakoane’s address at a symposium on constitutional reforms organised by the local advocacy group, Transformation Resource Centre (TRC), which centered on the theme ‘safeguarding the constitutional reforms from continuous litigation and political zero games.’

Posing a critical question to the symposium attendees, Sakoane challenged: “Is this national reform process a constituent-driven process or is it a process driven by those whose power is constituted by the constitution?”

He further delved into the confusion surrounding the reform process.

He stated: “I am putting that up front because, in my humble opinion, I feel like there is confusion here. You amend what is already there. An amendment amends.”

Drawing attention to the fundamental aspects that required attention, he redirected the discussion to the Plenary II Report, saying: “In my humble view, there are 16 areas, when I read that report, which the people said should be looked into.”

He indicated that those areas werere in chapter 1 of the report and elaborated on each of these areas including the powers of the prime minister, the bill of rights, prorogation and dissolution of parliament, public funds, decentralization, the office of the first lady, political conflict resolution mechanism, office of the king, formation of the government and coalitions, the preamble of the constitution, land, age of majority, chieftainship, religion and religious rights, application of traditional law in Lesotho, and official languages.

Continuing his discourse, he posed a crucial question: “Now the question is, given the magnitude and size of these constitutional issues of reform, can you pass them in one Bill called Omnibus Bill or don’t we need to change the constitution and write a new one altogether?”

Expressing concern over the current situation in Lesotho, he criticised the influence of external forces, stating, “The problem here in Lesotho is that this is a donor-driven process. That is where the problem is. That is why people say, ‘We are in a rush, we do not have time’. What is the rush? Whom are you pleasing?”

He questioned whether, during the consultations preceding reforms, the populace had demanded that donors’ opinions regarding the reform process should hold sway over decision-making.

“Did Basotho say that? I was not there when the people were being consulted. I was not there but knowing that the constitution belongs to the people, that is why many preambles start with the words ‘we the people’.”

He stressed the significance of ownership by the populace in the creation of a constitution, underscoring that the preambles of many constitutions do not start with the words ‘we the politicians’, ‘we Members of Parliament’, ‘we judges’, or ‘we the civil society’.

“They do not say so because this is the only law which is owned by the people and made by the people. The other laws are made by the representatives of the people, and those representatives do not have the constituent power to make a new constitution. That power belongs to the people,” he said.

Elaborating on the role of Parliament in amending the constitution, he clarified, “What Members of Parliament have is the power to amend the constitution, and that amendment is subject to limitations such as the observance of the basic structure of the constitution – things like separation of powers, rule of law, the democratic nature of the state, and independence of the judiciary.”

He emphasised the critical aspects of a constitution, stating: “Those are basic features of a constitution because if you have any constitution without those basic features, that is not a constitution. The only nation in history that had a constitution without those features was created by Hitler after commanding the majority of parliament in Germany, and we know what happened thereafter.”

He reiterated that the constituted power that members of Parliament have is subject to the limitations. “They could only amend the constitution within certain limitations and not beyond,” he said.

They cannot rewrite the constitution. They cannot overthrow the constitution. They cannot do that. Hence their amending power has procedural restrictions, for example, super majority, two thirds and in some instances, the referendum,” he said.

The Omnibus Bill contains most of the changes emanating from the country’s 2018-19 national dialogue on reform.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) instituted the dialogue after the turmoil in the country starting nearly 10 years ago.

The reforms are designed to stabilise the country by depoliticising the military, police and wider bureaucracy, and stabilising parliament, among other measures.

The previous parliament failed to pass the Bill until it was dissolved in July 2022. After it was dissolved, then prime minister Moeketsi Majoro declared a state of emergency paving the way for the king to recall parliament to adopt the Bill.

But the courts rejected that move, and Lesotho went to elections last October without the Bill enacted. All the political parties campaigning for the elections pledged to revive the Bill if elected to power

Earlier this year, Deputy Prime Minister, Nthomeng Majara, confirmed that the government intended to fundamentally restructure the Omnibus Bill.

But Majara later somersaulted and wanted to reinstate the Bill to the stage it had reached before the dissolution of the previous parliament.

However, the Appeal Court last month struck down the constitutionality of a parliamentary standing order that allowed the National Assembly to reinstate bills to their pre-dissolution stage.

Justice Kananelo Mosito, presiding over the Appeal Court, delivered a groundbreaking judgment deeming Standing Order No. 105B null and void on constitutional grounds.

“The following is ordered. The appeal is upheld. The order of the High Court is set aside and replaced by the following; circular no. 5 of 2023 and Standing Order no. 105B are declared constitutionally invalid and thus null and void,” Justice Mosito said.

The decree sharply restrains the National Assembly and even extends to the throne, binding His Majesty the King from enacting any bill that lapsed during the dissolution of the 10th parliament.

“The respondents are jointly and severally restrained from promulgating into law, any bill that lapsed at the dissolution of the 10th parliament. His Majesty the King of Lesotho is restrained from giving royal assent to any bill that was unfinished at the dissolution of the 10th parliament,” Mosito said.

This unprecedented decision stemmed from an application initially brought forth by the Yearn for Economic Sustainability (YES), a political party, Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) Lesotho, and journalist Kananelo Boloetse.

The High Court’s initial ruling undermined YES and MISA Lesotho’s standing in the litigation, recognising only Boloetse’s right to pursue the matter.

It sanctioned the National Assembly’s invocation of its constitutional powers under Standing Order No. 105B, legitimising the reinstatement of unfinished business from the prior parliament within the precincts of the current parliament.

Boloetse, aggrieved by the High Court ruling, went to the Appeal Court.

He is against the revival of the Omnibus Bill, and vehemently opposes its reinstatement to its pre-dissolution stage.

He adamantly argues for a complete reinitiation of the legislative process, shunning shortcuts in the bill’s path to enactment.

The TRC symposium also hosted professor Hoolo Nyane who delivered a paper titled ‘Lesotho can’t afford incremental changes to the constitution: it needs a complete overhaul’.

Nyane said the net effect of Boloetse’s case is that the reform process which culminated with the enactment of the Tenth Amendment has collapsed.

“Even attempts to resuscitate it have not succeeded. The insistence on short-circuiting the process is likely not to work procedurally. The easiest and most beneficial process is to make a new constitution and subject it to the vote of electors,” Nyane said.

“The country needs to thoroughly think about the substance of the new constitution and the process of adopting it,” he added.

Summary

- He indicated that those areas werere in chapter 1 of the report and elaborated on each of these areas including the powers of the prime minister, the bill of rights, prorogation and dissolution of parliament, public funds, decentralization, the office of the first lady, political conflict resolution mechanism, office of the king, formation of the government and coalitions, the preamble of the constitution, land, age of majority, chieftainship, religion and religious rights, application of traditional law in Lesotho, and official languages.

- He stressed the significance of ownership by the populace in the creation of a constitution, underscoring that the preambles of many constitutions do not start with the words ‘we the politicians’, ‘we Members of Parliament’, ‘we judges’, or ‘we the civil society’.

- Elaborating on the role of Parliament in amending the constitution, he clarified, “What Members of Parliament have is the power to amend the constitution, and that amendment is subject to limitations such….

Your Trusted Source for News and Insights in Lesotho!

At Newsday Media, we are passionate about delivering accurate, timely, and engaging news and multimedia content to our diverse audience. Founded with the vision of revolutionizing the media landscape in Lesotho, we have grown into a leading hybrid media company that blends traditional journalism with innovative digital platforms.