This story was supported by the Paballo-ea-Bophelo.

The schoolyard, often a stage for teaching, learning and the latest trends, is now an unlikely but powerful frontline in Lesotho’s fight against Human Papillomavirus (HPV).

Beyond the health clinic posters and radio announcements, a soft revolution is taking place, driven by the simple, convincing power of children sharing their vaccination stories.

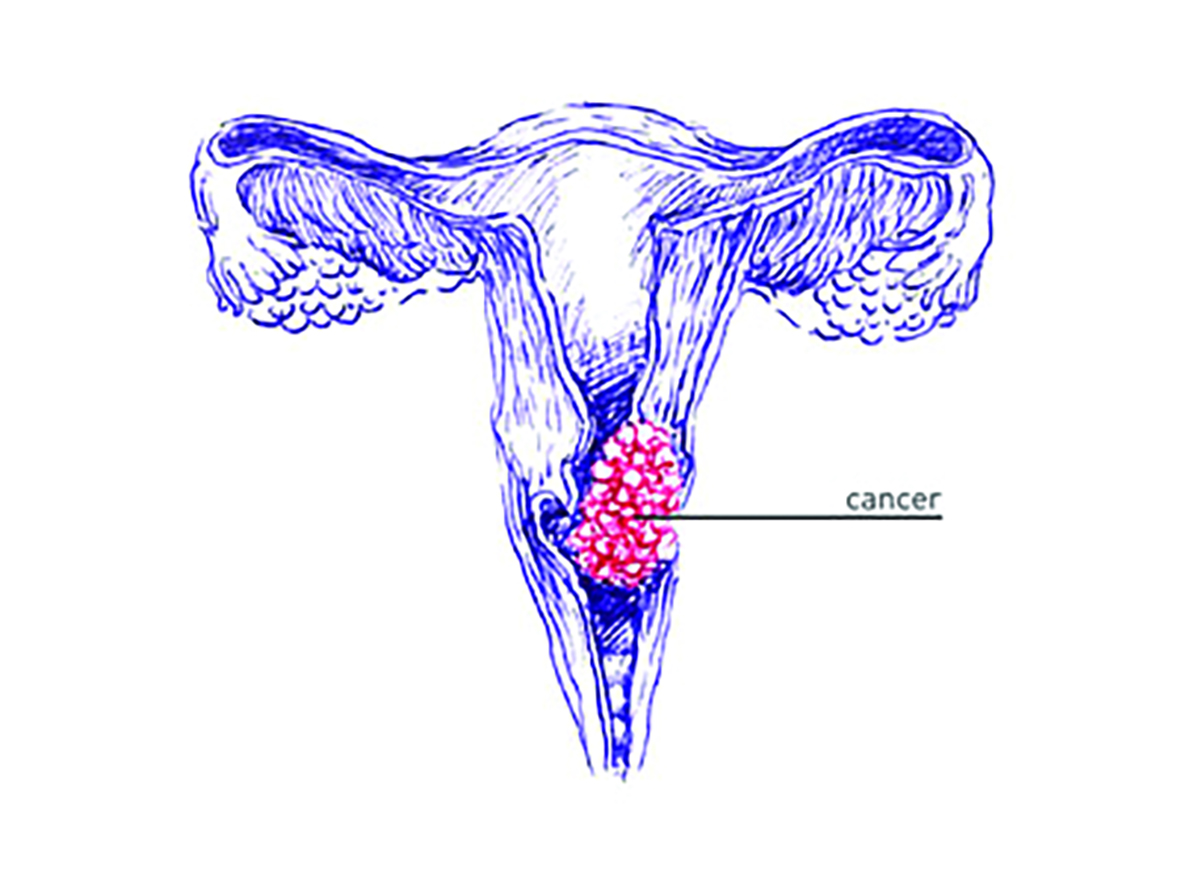

Lesotho has made remarkable strides in protecting its young girls from the Human Papillomavirus (HPV), the leading cause of cervical cancer.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), since re-launching a nationwide campaign in 2022, the Ministry of Health, with support from the WHO and partners, has achieved an impressive 93 percent HPV vaccine coverage among girls aged 9 to 14, surpassing its 90 percent target.

This success is a testament not only to robust public health systems but also to a hidden hero, the positive influence of children on their peers and, crucially, on their parents.

For students like Moleboheng Mphenetha, 12 years from Ha Paki, who attends school at Paki Primary school, the message about the HPV vaccine was clear and personal. “I was told that I should get vaccinated so that as I grow older, I should not get HPV.”

Mphenetha received her first dose at Paki Primary School during an outreach by Paki Health Center in 2022 and her second in 2024, reporting no negative side effects.

Her experience did not stop with her own protection; it became a mission. “She has done much to make sure that she encourages other students to get vaccinated,” says her aunt Lineo Pelebe, who was also an early source of information, having heard about the vaccine’s importance on the radio.

This combination of institutional messaging from the school and a reinforcing message at home empowered Mphenetha to become a vaccine champion among her friends.

Another student from Paki Primary School, Maleshoene Mosiee, 11 years of Ha Rajoko, recalls the moment she decided to get vaccinated in January.

“We were told by the school before that on that particular day, we were expected to bring along our health booklets.”

Though she felt a passing fatigue and sleepiness afterward, a common, mild side effect, she woke up fine, “as if nothing happened.”

What is compelling about Mosiee’s story is the clear chain of influence: School → Child → Parent → Peers.

“I told my mother, who had no objection but gave me the booklet and also kept reminding me that I had to get vaccinated,” she recounts.

Her influence then spread to her classmates. “To my friends, I just told them that my mother said we should vaccinate because we will not get HPV, and my friends got vaccinated, although we were afraid that the vaccines would be painful.”

This straightforward, relatable motivation from a trusted classmate, an appeal for shared protection and mutual bravery, was enough to overcome any fear of the needle.

The positive uptake is anchored in the relief felt by parents who have seen the devastating impact of HPV.

Morongoe Nkoti, years, a mother from Matukeng, embodies this sentiment. “I happily agreed for my daughter to receive the cervical cancer vaccination because I was aware of the gravity of the situation of cancer in the country,” she says.

Lesotho faces a serious cancer burden, with an estimated 541 women diagnosed and 362 dying from cervical cancer each year. The country logged an incidence of 49.9 cases per 100,000 women in 2020.

This alarming reality is what makes the vaccine’s promise so compelling to parents.

“I believe it is with vaccines like HPV that we will be able to protect our children against the disease, which is said to have taken the lives of many women,” Nkoti affirms.

She adds a key insight on the peer dynamic: “Our children can also influence other parents to get their children vaccinated when they tell them about their own experiences after being vaccinated.”

For these parents, their daughters getting the vaccine is “everything” a collective sigh of relief and a decisive step toward a future free from this preventable cancer.

The success of the campaign centers on smooth collaboration between the health system and the education sector.

‘Maseutloali Morebotsane, the Principal of Matukeng Primary School, notes the real influence of the students themselves. She believes that peer pressure in schools, where one student encourages others to get vaccinated, can dramatically boost coverage.

“If one girl is vaccinated and goes back home, where she tells her experience with the vaccine to other parents or her peers, it can motivate other parents to allow their children to be vaccinated,” Morebotsane explains.

She proudly reports that all eligible girls at Matukeng Primary School have been vaccinated.

Nthakoana Mokeretla, the Nurse-in-Charge at Matukeng Health Center, commends the groundwork laid by others. The health center, which serves more girls in primary schools, has reached its target, a feat she attributes to the key work of village health workers.

‘Matumelo Tumo, 43 years, a village health worker, confirms this crucial role. “When it comes to HPV, our work is to raise awareness about cervical cancer and let parents make the decisions for their children. But since parents have been receiving the message very well, that is why we have many girls vaccinated,” she states.

This extensive awareness campaign, often supported by messages from the Ministry of Health and its partners through the media, ensures parents are informed even before their children bring home the message that there will be a vaccination campaign at school and that they should seek permission from their parents.

Mokeretla agrees that peer-to-peer influence is effective, especially in an environment where parental refusal can be high. “In our area, we have not experienced the challenge of parents refusing to allow their children to be vaccinated. I believe this is because there has been much awareness or parents are seeing the deadliness of cervical cancer caused by HPV. The students are essentially the final, most trusted messengers,” she says.

Lesotho’s success in achieving 93 percent coverage by vaccinating over 139,000 girls since 2022 is a model for how a targeted health intervention can be amplified by social dynamics.

The story offers clear lessons on how positive peer pressure can be deliberately and effectively leveraged, creating platforms for vaccinated students to share their brief, positive experiences, not just the medical facts, with their classmates in a supportive, non-mandatory setting.

The Ministry of Health should also continue to clearly link the HPV vaccine to Lesotho’s goal of eliminating cervical cancer, as envisioned by the WHO’s Global Strategy.

Suzan Ramakhunoane from the Department of Family Health at the Ministry of Health says the Ministry has good collaboration with the Ministry of Education and Training. Together, they have developed, printed, and disseminated a School Health and Nutrition Strategy to ease the process of providing health services in schools.

“We have established structures together, District Immunisation Steering Committees (DISC) to plan together, get reports, and coordinate the health and nutrition work in schools,” she said.

She noted that people mostly seek advice and listen to their peers. “Our target for HPV vaccination is adolescents, who we have seen mostly copying their peers. If people look up to and believe in vaccines, then our uptake is positively affected and vice versa,” she said.

Ramakhunoane further emphasised that laws and regulations governing child protection should be strengthened to protect children from parents who prevent them from getting vaccines and other health services.

Summary

- According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), since re-launching a nationwide campaign in 2022, the Ministry of Health, with support from the WHO and partners, has achieved an impressive 93 percent HPV vaccine coverage among girls aged 9 to 14, surpassing its 90 percent target.

- This success is a testament not only to robust public health systems but also to a hidden hero, the positive influence of children on their peers and, crucially, on their parents.

- “I happily agreed for my daughter to receive the cervical cancer vaccination because I was aware of the gravity of the situation of cancer in the country,” she says.

Ntsoaki Motaung is an award-winning health journalist from Lesotho, specializing in community health stories with a focus on sexual and reproductive health and rights, as well as HIV. She has contributed to platforms like “Be in the KNOW,” highlighting issues such as the exclusion of people with disabilities from HIV prevention efforts in Lesotho.

In addition to her journalism, Ntsoaki serves as the Country Coordinator for the Regional Media Action Plan Support Network (REMAPSEN). She is also a 2023 CPHIA Journalism Fellow.